When one thinks of Italian cinema studied at universities, neo-realist films like The Bicycle Thief and directors like Antonioni and Visconti come to mind.

When one thinks of Italian cinema studied at universities, neo-realist films like The Bicycle Thief and directors like Antonioni and Visconti come to mind.

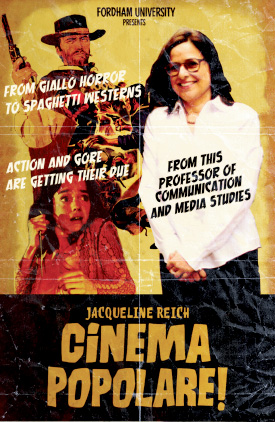

And yet entire genres—like Giallo horror and spaghetti westerns—also developed in Italy and inspired a degree of cult box-office success.

Now action and gore are getting their due from Jacqueline Reich, Ph.D., professor of communication and media studies—who also took up her post as department chair last fall.

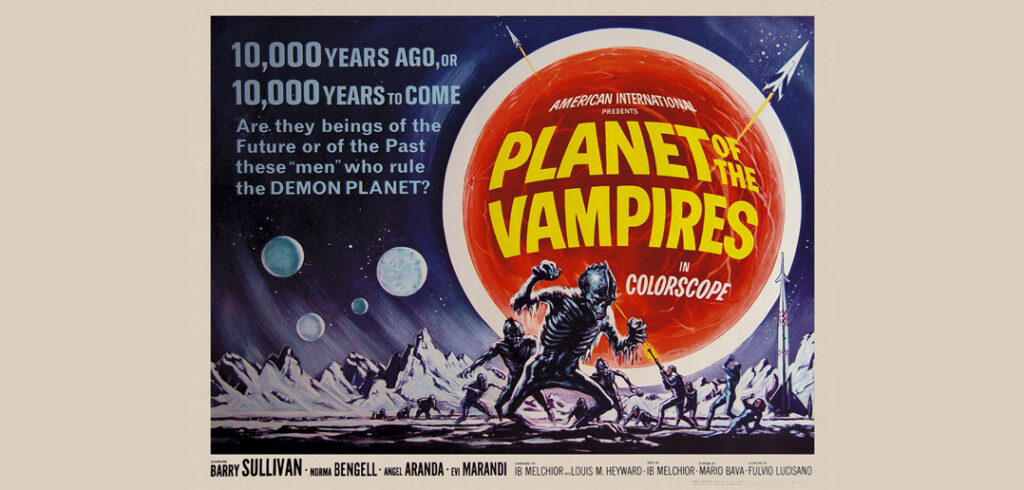

Reich said her “very strange trajectory” toward communications began with a bachelor’s in romance languages at Dartmouth, where she read Dante and Petrarch in the original Italian. She said she didn’t realize then that her “very classical preparation” would lead her to the work of Dario Argento, director of the 1977Suspiria, Mario Bava, director of the 1965 Planet of the Vampires, and many others.

When she attended the University of California, Berkeley, for her doctorate in literature, she said she didn’t realize that she could, in addition, take a minor in film studies. She soon became consumed with film history and ended up writing a film dissertation through the literature department.

As she finishes up her first year at Fordham and as head of the department, Reich said she will be meeting with faculty and staff this summer to take a “wholesale look” at the undergraduate curriculum, with an eye toward developing cross-disciplinary approaches. She used the recently developed major of New Media and Digital Design as a good example of what she’d like to see more of. The program is a joint endeavor with the departments of communication, computer and information sciences, English, visual arts, and the Gabelli School of Business. The major offers three tracks: commerce, information, and text and design.

“We identified all the courses that were out there in the University and figured out how we could combine them into a cohesive curriculum,” she said, “and it worked beautifully.”

The Department of Communication and Media Studies is also creating a public media masters program in conjunction with WFUV (90.7 FM, wfuv.org).

A native New Yorker, Reich’s route back to her hometown took a roundabout path, with stops at Trinity College in Connecticut, and Stony Brook University on Long Island, where she helped start the university’s film program.

Reich said that she’s not alone in her focus on Italy’s more popular cinema genres. She said that horror, comedy, and western films are now being approached by academics for what they reveal about the larger Italian culture.

“We used to concentrate on the neo-realists and the great directors, like Fellini,” she said. “But now we’re looking at film as a cultural commodity, as a very powerful industry, and how that industry interacts with discourses of gender, race, sexuality, and politics.”

The influence goes beyond Italy’s borders. She said that director Quentin Tarantino, in particular, frequently references the genres in his work.

“Django Unchained is really a spaghetti western meeting blaxploitation,” she said.

Reich’s research zeros in on film stars in particular. She said that the stars could be “read as texts with meaning.” Her first book focused on Marcello Mastroianni, titled Beyond the Latin Lover: Marcello Mastroianni, Masculinity, and Italian Cinema (Indiana University Press, 2004).

“I looked at him as a way that Italy worked through its own changing ideas of masculinity in a postwar society,” she said.

Reich is currently researching actor Bartolomeo Pagano’s film portrayals of the character Maciste, a serial role he developed so well that he came to be known simply as “Maciste.” She described him as the “first Arnold Schwarzenegger.” His character was a muscle man thrown into troubling situations from which he would fight his way out. Unlike other male serial stars, Pagano infused his character with irony and humor. Outside the studio, his image permeated the culture. Reich said that there is “overwhelming circumstantial evidence” showing that even Benito Mussolini was influenced by the character.

“If you put images of the two side-by-side, you’d be floored,” she said. “While we in the United States like to negate any political significance of our stars, in Italy they’re very ideologically ascribed, regardless of whether the star is apolitical or political—and you can see that influence in the politicians.”

Reich said that while most of the studios shaped the personalities of their stars, some—Maciste included—would outgrow their character. In the 1920s when Pagano wanted to leave the Italian movie system to begin a career in Germany, the studio sued to retain him and the rights to his name. The Italian court agreed with the studio that the star remained under contract, but it ruled that he owned his name because his body was so closely identified with the character.

Actress Sophia Loren was another star who closely managed her image, and whose work also engaged with the ongoing postwar changes in Italian society.

“She was this Mediterranean sexy ‘earth mother’ and was very much in contrast to the woman of the fascist period, who was mother, wife, and daughter—all very subscribed roles,” she said. “She made 12 films with Mastroianni, in which he always ends up [as]a puddle of mush.”

She said the postwar role reversal no longer relegated women to the domestic sphere, though arguments persist as to whether Italy is a matriarchy or patriarchy. While the government in Italy is “most definitely” patriarchal, she said, “you ask anyone who runs the country and they’ll tell you it’s the mothers.”