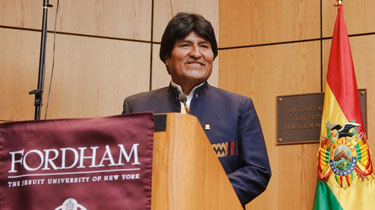

Photo by Ryan Brenizer

President Evo Morales of Bolivia visited Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus to share the story of his unlikely rise from poverty, and to promote his plans to help Bolivia’s indigenous poor.

Morales is a founder and member ofMovimiento al Socialismo (MAS, or Movement Toward Socialism), a grassroots political party that gained a foothold by calling for the nationalization of industry and fair distribution of resources in the energy-rich South American nation.

In his introduction of Morales, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said, “This may be our moment to be liberated from the notion that, as nations and individuals, we only speak to those with whom we fully agree, only those who are on ‘our’ side.

“To engage those who hold beliefs that may oppose our own is the first step in recognizing them as fully human, as part of the human family and worthy of our full and compassionate attention,” he said.

Addressing “The Realities of Democracy,” Morales told a packed house at the McNally Amphitheatre on Nov. 17 that he came from peasant stock, and recounted his family’s experiences as coca farmers in the 1980s.

During that decade, Morales said, the Bolivian government began working against farmers’ interests by instituting a U.S.-supported program to eradicate the coca crop, forcing the poor further into poverty by destroying their crops or buying their land at unfair prices.

The United States has a keen interest in deterring coca growth, as the plant is used to make cocaine.

Morales joined the coca union and became a leader in the cocalero movement, the union’s struggle to end eradication efforts and secure viable options for farmers. His opposition landed him in jail several times and led to his being severely beaten in 1989, he alleged.

But it also led to the realization, he said, that the movement had tremendous grassroots support.

“[But] it was not enough to have union power,” Morales said. “We needed a political instrument for liberation, to help us control all the natural resources. We were not people who were experts in politics; we were the indigenous people, the rural people, who decided to create our own political instrument.”

After being expelled from Congress in 2002, Morales ran for president later that year and finished second in a surprising show of support from the Bolivian people.

Joking, Morales credited his showing to the U.S. ambassador to Bolivia, Manual Rocha, who had called Morales a “danger” to further relations with the United States.

“Because of him, the people of Bolivia united behind me,” he told the audience.

He was elected president on the MAS platform in December 2005 with approximately 54 percent of the popular vote, becoming the nation’s first indigenous president; Morales is of Aymaran Indian descent.

Morales said that before he took office, private industry was reaping 88 percent of the gas revenue from the country while 12 percent went to the Bolivian people. Now, he said, the percentages are reversed.

Bolivia has the second-largest gas reserves in South America, after Venezuela.

“We’ve changed the social and cultural framework and now we have cultural institutions for the most vulnerable,” Morales said. “Before, people were slaves to government. Now, government is slave to the people.”

He also outlined key points he is seeking to add to the nation’s proposed constitution, which will be put to a national referendum in January. They include:

• providing education for students from first through eighth grades.

• creating a universal income for people over 60 in rural areas.

• ensuring that public services, such as water, electric and telephone, cannot be privatized.

• guaranteeing a pleura-national state.

• accepting no military bases within the nation’s borders.

• adopting a no-war policy with the nation’s immediate neighbors.

Morales acknowledged his detractors who “don’t accept the transformation,” he said. Last August, his opposition forced a recall referendum on his leadership, but more than two-thirds of the voters supported him.

“I’ve been accused of being the terrorist of terrorists,” Morales said. “I have to be frank—even the U.S. has sent military to work against the resistance and intimidate and create fear. But I said we have to start to get over these differences and work together. Also, we must live in peace and harmony.”

The event was sponsored by the Office of the President, the United Nations and Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.