As several Middle Eastern and North African nations aim to form more democratic, post-revolution governments, they may need to look beyond Western-style democracy for a model, said Kamal Y. Azari, Ph.D., GSAS ’88, a political science and Iranian studies researcher.

He proposed instead a community-centric democracy that relies on small, local governments, and promotes individual participation, while maintaining a balance of power and discouraging special-interest groups.

“We cannot look at the monolithic government and imagine that all the natural resources are equally divided,” he said, “but rather, each community will have their own way of development, and their own particular needs and goals.”

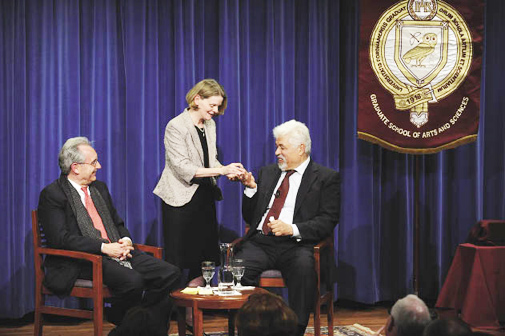

Photo by Chris Taggart

Azari spoke at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) March 30 spring Gannon Lecture, “Sandstorm: Interpreting the New Middle East and North Africa,” held on the Rose Hill campus.

Azari’s vision of democracy would include a familiar three branches of government at the national level—executive, legislative and judicial—and would add a fourth: A national trust, which would serve as a trustee for natural resources and a repository for national income and assets that citizens could borrow against.

An Iranian native, Azari was a Fordham graduate student who was about to head home when the Iranian Revolution caught fire. He remained in the United States, started an engineering firm and, in 1989, opened a winery in Petaluma, Calif. He also actively lobbied from afar for democracy in Iran’s Islamic republic.

This year’s lecture took the form of a question-and-answer dialogue with John P. Entelis, Ph.D., political science professor, director of the University’s Middle East Studies Program, and Azari’s mentor at Fordham. Entelis briefly recounted the recent “sandstorm” of uprisings that has ousted rulers in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen.

Editor of the Journal of North African Studies and a highly regarded expert on the region, Entelis challenged Azari’s governmental model on three counts: It seemed absent of cultural elements, appeared overly mechanistic, and closely resembled Western-style democracy.

Azari called the founding fathers “amazing visionaries,” so the resemblance to Western-style government was intentional, he said. But times have also changed.

“If the founding fathers were to be alive today, they would see [the]need for a fourth branch of government.”

Cultural diversity, of which tribalism is an important part in Iran and other Middle Eastern nations, would be addressed through “trust networks,” groups of people bound by common beliefs. “As these networks are integrated into public decision making, the government gains the support of the networks, and the networks, in turn, are tied to supportive, responsive government,” Azari co-wrote with Ali Mostashari, Ph.D., a professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, in a manifesto to be published in 2013.

Azari agreed that his model was mechanistic. “But it is a model,” he said.

Azari said he hopes for the opportunity to implement the model and to be able to use practical knowledge from its implementation “to improve the model.”

The former engineer likened the process to erecting a building. Regrettably, however, more time is often spent on erecting a building than on constructing a new government: that is why the U.S.-backed government in Iraq became corrupt and ineffective.

“We didn’t learn anything from it, and we went to Afghanistan and built a similar government,” he said.

Azari addressed current Western democracy, and how it, too, offers valuable lessons. In his manifesto, he cites “the unholy marriage of national governments with powerful global private interests, and the lack of rigorous oversight” that led to the 2008 financial crisis.

“We really have to have a model and we have to work on it,” he said. “[T]his is beyond academia.”

The Gannon Lecture Series, which began in the fall of 1980, brings distinguished individuals to Fordham to deliver public lectures on topics of their expertise. Fordham alumni endowed the series to honor Robert I. Gannon, S.J. president of Fordham from 1936 to 1949, who was an outstanding and popular speaker.