A man answered the knock at the door. The agents didn’t know that this was their suspect. After a tense exchange with the agents, he pulled out a revolver and shot and killed two of them, Anthony Palmisano and Edwin Woodriffe, GABELLI ’62. He fled the apartment through a window, and city police and FBI agents captured him a few hours later. The murder of the two agents still resonates. Both were under 30, part of a tight-knit cohort of young agents in the FBI’s Washington field office, some of whom vividly recall the events of that day, January 8, 1969. And the killings were shocking for another reason. Woodriffe, 27 at the time, became the first black FBI agent to die in the line of duty.

For burial, he was brought back to his native Brooklyn, back to the city he loved, where he had worked his way through Fordham before launching his career in government service.

This April, the story of the earnest, witty agent who died too soon came back into the spotlight as the city honored him by making his name a fixture on the urban landscape. In a well-attended ceremony on a Brooklyn street corner, in the heart of the neighborhood where Woodriffe grew up, his immediate family spoke in remembrance of a radiant young man whose spirit seemed, somehow, to be present still.

A Child of Immigrants

Like so many New York stories, Edwin R. Woodriffe’s begins with immigration—his parents came to America from Trinidad when they were either in their teens or barely out of them, said Woodriffe’s daughter, Lee Woodriffe, of Lithonia, Georgia. They ran a dry cleaning shop in the struggling Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, getting up early every day—“no time off, no sick days, no nothing”—and instilling a strong work ethic in their children, she said.

The youngest of three boys, Woodriffe helped out at the dry cleaner’s after school and doted on his parents, Lee Woodriffe said. He was an altar boy at nearby St. Peter Claver Church, where he met his future wife, Ella Louise Moore, during Christian confraternity classes.

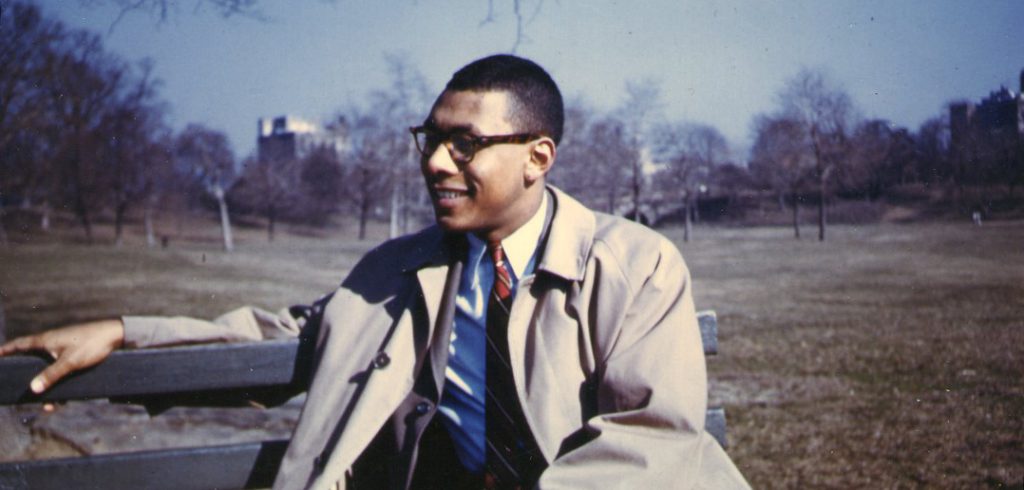

After graduating from Brooklyn Preparatory School, he earned a degree in accounting at Fordham’s City Hall Division at 302 Broadway, where he was vice president of the philosophy club. He paid his way by working as a police cadet and as an elevator operator at Macy’s, his daughter said. Upon graduation, he and Ella were married, and they had two children, Lee and her brother, Edwin Woodriffe Jr. Lee was only 5 when her father was killed, but learned from others what he was like. He was a jazz lover who would sometimes play his saxophone on the roof of the building where the family lived, she said. A voracious reader interested in religion and philosophy, he was a deep thinker, which was apparent from his conversation and his humor, she said.

The idea of working in law enforcement had taken hold when he was young; he admired his older brother for being a New York City police officer. After working for the Treasury Department in enforcement, he joined the FBI in 1966. Sometimes he would sign letters “Eliot Ness,” Lee said, describing her father as “really good-natured, and just always cracking a joke.”

In the FBI’s Washington, D.C., field office, he was low-key and decisive, “a very classy individual” who was courteous toward crime suspects, said Ed Armento, a retired agent who trained under Woodriffe for a week.

Lee Woodriffe said her father was one of only a handful of black FBI agents. Retired agent Robert Quigley, GABELLI ’62, recalled working with three black agents besides Woodriffe in the Washington field office. Given Woodriffe’s talents, “there is no doubt in my mind that [he]would’ve been one of the top FBI executives had he lived,” Quigley said.

He recalled a story of solidarity against racism that was told to him: When Woodriffe was an FBI trainee in Washington, D.C., he and his classmates went to suburban Maryland to rent apartments, but they all pulled out of a pending housing contract when told Woodriffe would be barred. “The other agents were aghast,” Quigley said, so they sought housing elsewhere.

A Tragic Day

Quigley remembers the day when agents learned of a bank robbery by Billie Austin Bryant, an escaped federal prisoner. Woodriffe, Palmisano, and another agent went to the apartment where they had heard Bryant’s wife or girlfriend lived, said Quigley, citing reports prepared afterward. The agents couldn’t have known it was Bryant who opened the door when they knocked—“They have no photograph, no idea what he looks like,” Quigley said. “Back in those days, all we had were radios in the car. There was no way to send a photo.”

Bryant told the agents the woman they were seeking wasn’t there. When they asked to come in and wait for her, he refused and started to close the door. Woodriffe put his foot in the door to stop him, and Bryant pulled out his revolver. Woodriffe and Palmisano never got a chance to pull their firearms, said retired agent Charles Harvey, who tried to revive the two agents soon after.

Bryant surrendered to a police detective six hours later, after being tracked down to an attic in a building where someone had reported noise, said Quigley, who was there when Bryant was captured. Bryant was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences with no chance of parole.

The 50th anniversary of the two agents’ deaths was commemorated in Washington in January by the bureau’s Washington field office and the Society of Former Agents of the FBI. Harvey spoke at the event. “Our job is to never forget,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, another remembrance had taken root.

A Street Renamed

St. Peter Claver Church sits at the intersection of Jefferson Avenue and Claver Place in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Lee Woodriffe spearheaded the two- year effort to have the City Council co-name the segment of Jefferson Avenue starting at that intersection in honor of her father, hoping to keep him present in a part of the city that was important in his life, she said.

“I did not want his final resting place in people’s minds to be in Cypress Hills Cemetery,” she said. “It’s very important to me that [his story]come full circle, but come full circle in the right way.”

The co-naming sends an inspiring message, she said. “Here is somebody who came from an impoverished area, odds stacked against him, but through perseverance and diligence and having integrity and wanting to do better, rose up through the ranks and really made something of himself. It’s a story of hope, and what you can become.”

On April 26, FBI Special Agent Edwin R. Woodriffe Way was formally christened in a ceremony attended by FBI agents, New York City police, city officials, clergy, and friends and members of Woodriffe’s family, including his widow, Ella Woodriffe.

“There’s a saying that hatred corrodes the vessel it’s carried in, but today I have no hatred,” she said. “I speak with heart-filled joy and thanking God for allowing all of us to be here in attendance as a testament to my husband’s memory.

“His story began right here at St. Peter Claver Church,” she said. “Edwin went to school here. He went to church here. He was an altar boy here. We met as teenagers here. … We were married here, we had two children, and lastly, he was funeralized here. He will be forever remembered in our hearts.”

Edwin R. Woodriffe Jr., who was 6 when his father died, lacks vivid memories of him. “There are photos and stories from friends and family, but the nuances are lost,” he said at the ceremony. “What was his favorite color? I don’t know. I have one of his high school essays on basketball. Were the Knicks his favorite team? I don’t know, and if I did, I don’t remember.

“But he got a B+, by the way, on the paper,” he said, to laughter.

“The thing I remember most is the idea of him represented inside the family,” said Woodriffe, whose mother got help from extended family in raising him and Lee. “I feel blessed that my father’s sacrifice was a part of inspiring my sister and I to be the adults that we are today. And on the 50th anniversary of his passing, I’m honored to see his name on this corner, where his story can continue.”

Auxiliary Bishop James Massa of the Diocese of Brooklyn also spoke at the ceremony. He said the newly unveiled street sign is a reminder “that a great New Yorker once lived among us and overcame racial barriers in order to serve, in order to protect the vulnerable and contribute to the common good of our nation.”