In her debut memoir, Dionne Ford takes readers along for an emotional ride as she crisscrosses the country to find her enslaved ancestors—and herself.

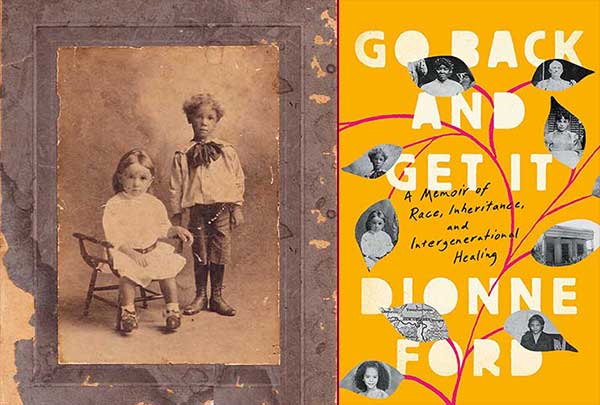

The day Dionne Ford turned 38 years old, she came across an old “family” photo on the internet, a picture she’d never seen before. It shows her great-great-grandfather Colonel W. R. Stuart, a wealthy Louisiana cotton broker; his wife, Elizabeth; Ford’s great-great-grandmother Tempy Burton, who was given to the Stuarts by Elizabeth’s parents as a wedding present; and two biracial-looking young women, assumed to be Tempy and the Colonel’s children.

The discovery prompted Ford to embark on a yearslong journey from New Jersey to Louisiana to Virginia and back again, searching for clues into the life of Tempy and her six children, plus whoever else she could find to uncover (and understand) her roots. Last April, she published Go Back and Get It: A Memoir of Race, Inheritance, and Intergenerational Healing, a compact yet expansive look at her trek back in time to search for her family history. And a trek it was.

“If you are going to look for your enslaved ancestors,” Ford writes in the book’s prologue, “you will have to look for the people who enslaved them. … This is a study in contrasts. Shadow. Light. Black. White. Joy. Pain. Victim. Perpetrator. You will find ephemera—editorials, photographs, wedding announcements—and atrocities—lynched uncles, your people as property in someone’s will, deed, or mortgage guarantee. You will also find the living— third cousins once removed, fifth cousins straight up, and descendants of the family that forced your family into slavery.”

The book’s title refers to a kind of pilgrimage, called sankofa by the Akan people of Western Africa. “It is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten,” writes Ford, who earned a B.A. in communications and media studies from Fordham College at Lincoln Center in 1991 and an M.F.A. in creative writing from New York University in 2016. As she digs deep into the 19th century, she also contends with personal trauma: the childhood sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of a close relative and the alcoholism that helped her cope. And she evokes a riot of emotion for readers, perhaps particularly Black readers, as she grapples with the history of slavery and the ways in which its aftermath affects generation after generation.

At the beginning of the book, you talk a bit about wanting your older daughter, Desiree, to embrace her roots. Did she? How did your research affect her, your other daughter, Devany, and your husband, Dennis?

This definitely affected my family. I took my girls with me on research trips, so they were a part of this journey. I do think that they both had a certain pride in just knowing about this side of their family’s history, and particularly about the enslaved women.

My cousin made this game for the kids to play that had all the ancestors on cards, and everybody always wanted to be Tempy. I felt like they already were positively internalizing their female ancestors’ lives. I think it’s always grounding for people to know as full a story as possible.

Throughout the book, you write about how language can fall short when you’re doing this kind of research—and writing about it. What advice would you give to other Black people who want to investigate their own family history? How should they get started?

Talk to your elders. Find a respectful way to let them know that you’re interested in your shared history, and you’d like to set aside time to just ask them some questions about it. They’re gone before we know it, so it’s so important.

Then get yourself some kind of group because it’s painful and hard if you’re dealing with people who were enslaved or oppressed, so working with other people who are also in earnest, who can be a support to you and you can support them, is great. The group AfriGeneas is for people who are of African descent. And if you also can find a research partner in your family, that’s really wonderful. Don’t be in a hurry, and be open-minded because you’re probably going to find a lot of things that you didn’t expect—and maybe that you didn’t want to, either.

Beyond personal reasons, why did you write this book?

James Baldwin wrote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” In my experience, not only can nothing be changed until it’s faced, but somehow the more I try to avoid a thing, the more power it has over me. Something fundamentally shifted in me through this process of confronting my family’s history and my own. So, by organizing my experience into a narrative, I hoped to offer that to readers: the possibility for some fundamental shift by facing whatever it is in their life they would rather avoid.

Is there a particular ancestor that you now feel most connected with as a result of your research?

Probably Josephine, my dad’s grandmother.* She wrote articles in the newspaper—she was so spicy. Because of the things that she wrote, we were able to find so much more information about our family, so I think that makes me feel just a special connection to her.

How did you choose what research to cite and discuss?

I chose to include things, in the end, that were specific to my story—if they were specific to Louisiana slavery, women in slavery, or my own story—but it was hard.

For example, I kept From Slavery to Freedom, [John Hope Franklin’s classic history of African Americans], because it dealt with the Sterling family, who had enslaved some of my family. There were so many wonderful texts that did help me get a better understanding.

What would you say has been the most unexpected response to your memoir?

I have had a couple of strangers—and friends, too— say that they really appreciated me talking about the sexual abuse. One woman, in particular, said that had happened to her and that after she read my book, she actually sought out a survivors group and went for the first time in her life. That was very humbling and moving, and I felt so grateful that anything that I could write might actually help somebody find a bit more peace or serenity.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on adapting my book into a limited series. There are things you can do visually that you can’t do on the page—things that I didn’t feel comfortable doing because it was a memoir, and I really wanted to stick to as much of the truth that I was able to back up as possible. Now I’m having a little bit more fun and envisioning what it would’ve been like for them living at that time. I’m also going back to the novel that I was supposed to write as my MFA thesis at NYU but had ditched so I could work on my memoir.

I’m a member of the New Jersey Reparations Council, too. The state has been dragging its feet on passing a bill to just study reparations, so the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice just said, “You know what? We’re not waiting for you. You guys take too long. We’re convening our own council.” And they invited me to participate. I’m really excited.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Sierra McCleary-Harris is an associate editor of this magazine.