In October 2012, Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha—17th-century Mohawk maiden, patron of ecology and the environment—will become the first-ever Native American saint in the Catholic Church. Who was she? What does her canonization mean? And was her intercession responsible for a miracle at Fordham more than 80 years ago?

The last game of the 1931 season had all the makings of a classic. Fordham and Bucknell, each team undefeated and among the best in the country, took the field before an estimated 30,000 football fans at the Polo Grounds in New York City. The Nov. 21 contest, which Bucknell won by the slimmest of margins, was especially brutal. Two of Fordham’s tackles had to be carried off the field; only one would survive.

Cornelius “Connie” Murphy suffered a head injury and was taken to Fordham Hospital. Replacing him was junior John Szymanski, who, late in the game, slammed head-on into a Bucknell player with a blow so severe that for months, he lay in a bed at Fordham Hospital, fighting for his life.

Doctors diagnosed him with a cerebral hemorrhage, which had paralyzed his left side. Murphy was released from the hospital, seemingly recovered, but on Dec. 2, he collapsed suddenly and died. On Dec. 9, Szymanski’s surgeon announced there was no hope for his recovery. His parents were summoned; he received last rites.

The student body, already grieving Murphy’s untimely death, began praying a solemn novena. They asked God to heal their beloved classmate through the intercession of Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th-century Mohawk virgin who was persecuted for her Catholic beliefs and died at a young age. Szymanski made a full recovery.

Kateri, or Blessed Kateri, as she has been known since her beatification in 1980, will become the first-ever Native American saint when the church canonizes her on Oct. 21 to much fanfare and jubilation among her devotees. In December 2011, the Vatican removed the last obstacle to her sainthood by formally attributing a miracle to her—the sudden recovery in 2006 of a boy whose face had been attacked by a flesh-eating virus.

But there was a time early on in her canonization process when many thought Szymanski’s recovery might have been her first official miracle. Though dozens of other stories of Kateri’s intercession were submitted to the Vatican, an Associated Press article from 1936 said that “one of the most important of these is that of John Szymanski.” It was an early juncture on a long and winding road to sainthood that began more than three centuries ago in what is now upstate New York.

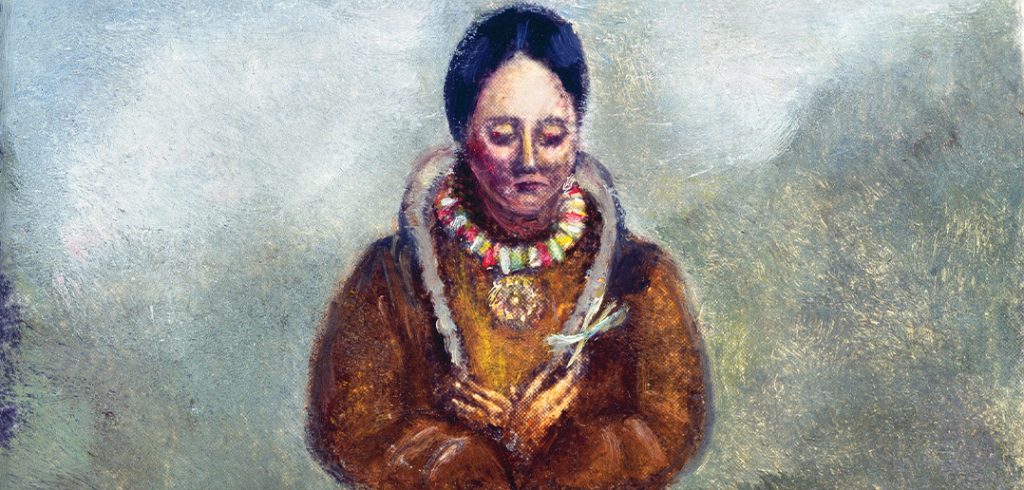

Kateri Tekakwitha was born in 1656 in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon (modern-day Auriesville) to a Christian Algonquin mother and a Mohawk chief father. It was a time of violent warfare between the Iroquois and Huron people, and tensions between the natives and French Jesuit missionaries. Eight Jesuits, known as the North American Martyrs, were killed in the area during the decade before Kateri’s birth. (Martyrs’ Court, a residence hall on Fordham’s Rose Hill campus, was dedicated to three of the martyrs—Saints Isaac Jogues, John LaLande, and Rene Goupil—in 1951.) Smallpox ravaged Ossernenon when Kateri was 4, killing her parents, scarring her face severely and damaging her eyesight. She was given the name Tekakwitha, which means “she who bumps into things.” Despite being adopted by an anti-Jesuit uncle, she always showed an interest in her mother’s Christian faith. She refused to marry and converted to Catholicism at 19 with the help of Jesuits who baptized her in memory of St. Catherine of Siena (hence her name “Kateri”).

Villagers who fiercely rejected the missionaries scorned her for her Christian faith, denying her food when she refused to work on Sundays. She fled to a Jesuit mission near Montreal, where she joined a community of celibate Iroquois women and practiced self-flagellation to affirm her faith. She was said to have spent much time in the woods, and was considered something of a mystic. In a weakened state from illness and her self-inflicted wounds, Kateri died in 1680 at the age of 24. Witnesses said that upon her death, her smallpox scars disappeared, leaving her skin smooth and glowing.

Though recent news stories of her upcoming canonization may be the first introduction to Kateri for some, the church and other Catholic institutions have long honored this “Lily of the Mohawks,” as she is known. In an essay published in the April 2004 issue of The Catholic Historical Review, Allan Greer, professor of history at the University of Toronto and author of the book Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits, writes: “[B]eginning almost immediately after her death, she became the object of a cult among Native and French-Canadian Catholics.”

The case to make Kateri an American saint, however, would not begin for another 200 years. It was first proposed at an 1884 meeting of U.S. bishops in Baltimore, Md., at a time when the American Catholic Church was battling image problems. As immigrants poured in from Ireland and southern Europe, Greer writes, “old patterns of religious prejudice united with thoroughly modern class problems to produce an upsurge of native anti-Catholicism.” The bishops saw in Kateri a perfect “symbol connecting Catholicism to Nature and the Land and to a primordial American essence that was the antithesis of industry, immigration, urban grime and class conflict.” At the same time, Catholic missionaries were subjecting Native Americans to forced assimilation in government-run boarding schools. Although the bishops “forwarded to Rome a brief for beatification” in 1884, Greer notes that the “Congregation of Rites waited decades before instituting formal proceedings.”

Finally, in 1931, a postulator for Kateri’s sainthood was appointed and set about the business of convincing the Vatican, through stories of Kateri’s good works and intercession, that she was worthy of canonization.

To be declared a saint, one must have been martyred for the faith or lived a life of heroic virtue. If the pope concurs, he proclaims the person “venerable.” To be beatified and given the title “blessed,” a miracle must be attributed to the venerable person. Canonization requires a second miracle. Though it sounds complex, Pope John Paul II simplified this process in 1983. Prior to that, additional miracles were often required.

Pope Pius XII declared Kateri to be venerable in 1943. In 1980, Pope John Paul II, responding to the great desire of Native American Catholics and perhaps to the church’s long-held wish for an aboriginal North American saint, waived the requirement of a first miracle and beatified Kateri. (Some called the deathbed disappearance of her smallpox scars a miracle, but the church never approved it.)

It was not until December 2011 that Pope Benedict XVI officially approved a miracle in Kateri’s name. It was the 2006 recovery of 5-year-old Jake Finkbonner of Ferndale, Wash., whose face was attacked by a flesh-eating virus after he cut his lip playing basketball. His Lummi Indian parents and their loved ones prayed to the Mohawk maiden, and the fast-moving virus stopped abruptly. He was cured.

For sainthood, miracles are examined by a team of medical experts and theologians, and in the case of medical recovery, they must be found to be complete, instantaneous, and lasting. Church postulators worked for three years gathering evidence to prove Jake’s case met these requirements. Though his face is badly scarred, today Jake is a self-proclaimed “completely normal” 11-year-old boy, according to his personal website, who loves basketball and video games.

Three-quarters of a century before Jake’s fateful game, another young athlete set out to play football without a care in the world, except maybe that primping with his teammates for their evening dates would make them late to the Polo Grounds.

“An order was given to the cabbie for a bit of fast stepping,” John Szymanski wrote years later in an unfinished manuscript. “Sneaking in and out of slow traffic we began to jostle each other jokingly about how homely the other looked—a college boy prank at Fordham.”

When they took the field, spirits were high. “Twenty-two huskies forgetting their cares were raring to go!” he wrote. “Twenty-two gladiators fighting for glory and fame!”

But the glory faded fast, and he soon found himself in Fordham Hospital, a now-demolished city hospital that once sat on Fordham Road.

“The ward was all astir,” Szymanski wrote in his memoir, which ends abruptly after 14 pages without mentioning Kateri. “People seemed to have arrived to inquire about us. Little did I care; I was still half in a fog.”

For nine days, students asked for Kateri’s intercession for the popular gridiron star. They prayed after 7:30 a.m. Mass and at four other times, according to Kateri Tekakwitha, The Lily of the Mohawks: Her Life and Remarkable Favors Received Through Her Intercession by John J. Wynne, S.J., of Fordham. The booklet includes testimony from several witnesses to Kateri’s intercessions, including William A. Whalen, S.J., dean of discipline at Fordham at the time, who wrote about the prayers for Szymanski.

The devoted group recited “ten ‘Our Fathers,’ ten ‘Hail Marys,’ and the prayer on the leaflet that is distributed by Father Wynne, the Vice-Postulator of the Cause,” Father Whalen wrote. Several convents of nuns joined in the novena as well, and in the hospital, a relic of Kateri was applied to Szymanski “each day during the novena and every day since by his confessor.”

The New York Times reported on Dec. 14 that although Szymanski was still “on the serious list,” his condition was improving—a vastly different prognosis than he’d received just days earlier. He was discharged on Feb. 9, 1932, and went on to graduate from Fordham in May 1934. People hailed his recovery as a miracle. Many believed that Blessed Kateri was responsible.

In modern-day America such devotion to a particular saint, or almost-saint, might seem strange. The practice was much more common when immigrant families felt a devotion to a saint from their home country, said Angela O’Donnell, acting director of Fordham’s Curran Center for American Catholic Studies.

“If people felt especially connected to a place, they felt connected to that saint,” said O’Donnell. For the Native American Catholic community, then, Kateri’s sainthood will be affirming, especially since “there is a legacy, unfortunately, of less than positive experiences when the missionaries came over.”

Former Mohawk Chief Tom Porter has no plans to join in the Kateri revelry, however. He bases his spirituality in the beliefs of “my-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother,” that is, “a worldview based on nature, that God is in every living thing.”

“That saint stuff doesn’t have any value in our traditions,” he said, though he is “happy for the Indian natives that are Christians that have worked so long for this.”

Sister Kateri Mitchell, who is Mohawk and a member of the Sisters of St. Anne, feels that Tekakwitha’s recognition will help to heal the wounds of the past.

Native American Catholics have felt that they have “always been on the edge, or the fringes,” of the church, said Mitchell, who directs the national Tekakwitha Conference, based in Great Falls, Mont., a Catholic ministry among Native Americans.“That’s why our people are overwhelmed with joy at this news.” Mitchell, who took Kateri’s name when she entered the convent, will lead a group of “hundreds” who plan to travel to Rome for the canonization on Oct. 21.

John Szymanski once dreamed of his own trip to the Vatican, according to his nephews. Though it is unclear if he ever went, he celebrated Kateri in his own quiet way. There was no doubt in his mind, they said, that she was responsible for his recovery.

“He believed it was attributed to the prayers,” Stan Kubas said of Szymanski, his mother’s brother, who died in 1984. “He believed he had a special relationship with her.”

Kubas worked with Szymanski, who was head of the sewer authority in New Britain, Conn., for more than 20 years. When his uncle died, he found himself in possession of Szymanski’s unfinished manuscript. He laughs at its tales of young female admirers, typical of Szymanski’s “healthy ego.” (“It dawned on me that I had a date for the evening with a beautiful New Rochelle College senior,” Szymanski wrote of his first night in the hospital. “However, I guess it won’t be the first time a girl was disappointed.”)

has entirely disappeared, and, consequently, he has been able to walk around the ward for the past few weeks.” The student paper also reported that during the holidays, Szymanski received “many baskets of fruit and boxes of candy,” and 257 “greeting cards sent by undergraduates,

alumni and well-wishers.”

After his turn as a ladies man and fallen football hero, Szymanski became quite a devoted Catholic. A Pennsylvania newspaper ran a story in August 1934, just after he graduated, about his preparing for the priesthood in a Washington, D.C., seminary, though his nephews knew nothing of this. He married, however, in 1937 and became active in his New Britain Polish parish and the Knights of St. Gregory. Dave Kubas, Stan’s brother, recalled that his uncle made at least two trips to Kateri’s birthplace at the Shrine of Our Lady of Martyrs in Auriesville, about 45 minutes northwest of Albany.

The shrine is located on the site of Kateri’s village of Ossernenon and pays tribute to her as well as to the three North American martyrs who were killed there. Beth Lynch is the shrine’s events coordinator. She and the rest of the staff are planning a big celebration for Kateri’s canonization day on Oct. 21.

“Of course we’re overjoyed by it,” she said. “It’s been so long in coming. Invariably every week somebody would stop in and say how Blessed Kateri had interceded for them. There’s a constant flow of testimony.”

Fordham alumnus James Downey, FCRH ’70, visited the Auriesville shrine about six years ago. In leafing through some binders there, he came across some newspaper clippings about Szymanski and the Fordham Rams. He was moved by the story and wondered if Szymanski’s case was ever approved as a miracle. But upon further contemplation, he found himself wondering if it mattered.

“There are just lots of miracles out there,” said Downey, a lawyer in Warrenton, Va. If the Vatican is looking for two or three, he mused, “well, there could be a million.”

Downey, a catechist at St. John the Evangelist in Warrenton, said the openness of those asking for a miracle plays a significant part in its taking place.

“The element of faith is the ingredient that will give the miracle the ability to occur,” he said. He was reminded of the song “A Hundred Million Miracles” from the 1958 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The Flower Drum Song.

“A hundred million miracles are happ’ning ev’ry day,” the song goes, “and those who say they don’t agree, are those who do not hear or see.”