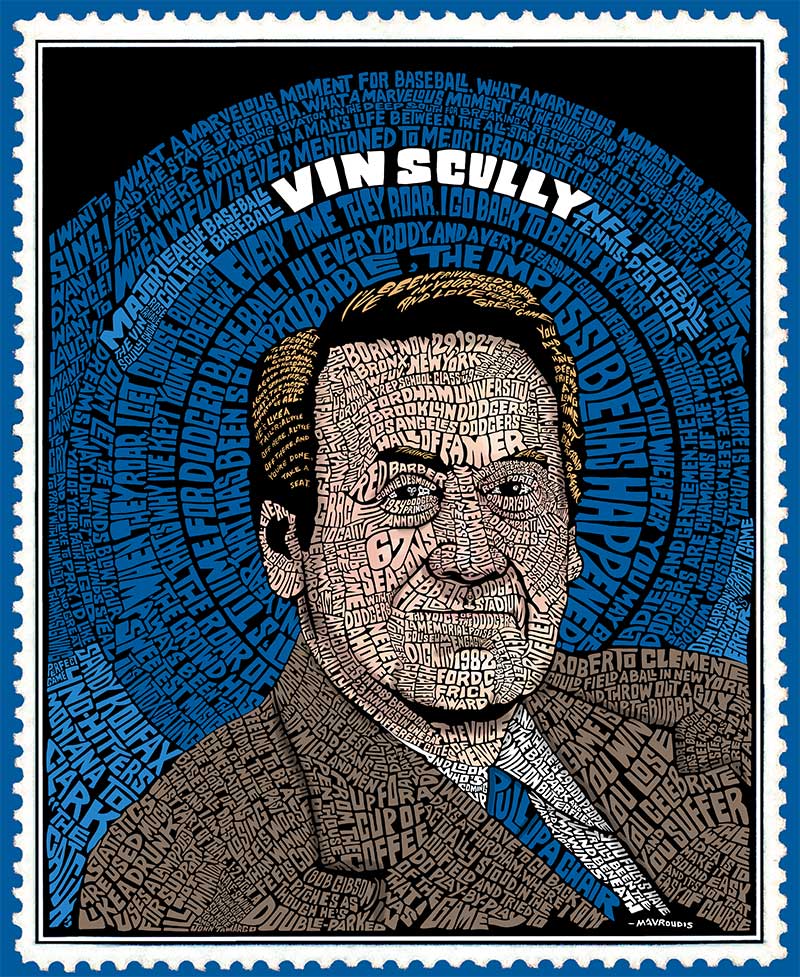

Shortly after Scully died on August 2, 2022, at the age of 94, Sports Illustrated writer Tom Verducci used the Latin phrase eloquentia perfecta, or perfect eloquence, to describe Scully’s gift and well-honed craft. “Freshmen at Fordham, including Vin Scully, class of 1949, take a seminar class taught by the most accomplished faculty called eloquentia perfecta,” Verducci wrote. “It emerged from the rhetorical studies of the ancient Greeks, codified in Jesuit tradition in 1599. It refers to the ideal orator: a good person speaking well for the common good. It is based on humility: The speaker begins with the needs of the audience, not a personal agenda. Vin Scully was that ideal orator. A modern Socrates, only more revered.

“He was an amazing firsthand witness and chronicler of history. … And yet never did Vin place himself above the people and events he was there to chronicle.”

In a career spanning seven decades, Scully described some of the most memorable moments in baseball. He was erudite and eloquent, with exquisite timing and an ability to frame the drama as it unfolded. He could weave anecdotes about the players, literature, and history into the flow of the game, interrupting himself to describe a pitch without losing the thread of his tale or his listeners’ attention. But he also knew when to go silent and let the magical moment—and the roar of the crowd— speak for itself.

He received numerous awards throughout his career, including induction into the broadcasters’ wing of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, an Emmy Award for lifetime achievement in 1996, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2016. “The game of baseball has a handful of signature sounds,” Obama said at the White House ceremony. “You hear the crack of the bat, you got the crowd singing in the seventh-inning stretch, and you’ve got the voice of Vin Scully.”

The Early Years

Scully was born in the Bronx after his parents immigrated from Ireland. He grew up in Washington Heights and attended Fordham Preparatory School. After graduating in 1944, he served briefly in the Navy before enrolling in Fordham College at Rose Hill, where he majored in communications. In 1947, he became one of the original voices of WFUV, the University’s radio station. He penned a sports column in The Fordham Ram, worked as a stringer for The New York Times, and sang in the Shaving Mugs, a campus barbershop quartet. For two seasons, he played outfield for the Fordham baseball team.

Five decades later, on May 20, 2000, Scully returned to Rose Hill to receive an honorary degree from the University and deliver the commencement address. He told graduates that the “four-letter words” he associated with Fordham were “home, love, and hope.” And he didn’t put himself above his audience: “It’s only me,” he said, “and I am one of you. … I walked the halls you walked. I sat in the same classrooms. I took the same notes and sweated out the final exams; drank coffee in the caf and played sports on your grassy fields.”

But Scully’s favorite place to be was behind the mic. He called Fordham baseball, basketball, and football games for WFUV. And in a 2020 documentary on the station’s celebrated sports department, he joked that he would even call games to himself while playing for the Rams. He recalled listening to games as a kid and being “so thrilled by the roar of the crowd that first, I loved the roar. Then I wanted to be there, and eventually I thought I would love to be the announcer doing the game.”

The Voice of the Dodgers

After graduating from Fordham in 1949, Scully spent the summer at a CBS radio affiliate in Washington, D.C., before he returned to New York to speak with the network about working there. Just a few days later, he received a call from Red Barber, the legendary CBS sports director and broadcaster, asking him to cover a college football game that Saturday. By spring, the 22-year-old Scully had joined Barber in the Brooklyn Dodgers broadcast booth. When Barber left to work for the Yankees following the 1953 season, Scully became the team’s primary announcer, a position he held when the franchise moved to Los Angeles for the 1958 season and kept until he retired in 2016.

The highlights of his career are too numerous to recount in full, but in 1955, he called the final out of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ only World Series victory. He described Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series, calling it “the greatest game ever pitched.”

He was behind the mic for another perfect game a decade later, by the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax on September 9, 1965. That game was not televised, but Scully’s descriptive, evocative call of the last inning helped listeners see and feel the drama. “And you can almost taste the pressure now,” he said after the second strike against the inning’s leadoff hitter, Chris Krug. “Koufax lifted his cap, ran his fingers through his black hair, then pulled the cap back down, fussing at the bill. Krug must feel it too as he backs out, heaves a sigh, took off his helmet, put it back on, and steps back up to the plate.” Moments later, Scully said, “And there are 29,000 people in the ballpark and a million butterflies.”

On April 8, 1974, the Dodgers traveled to Atlanta to play the Braves, whose veteran slugger, Hank Aaron, was one home run away from breaking Babe Ruth’s record of 714 career home runs. In the fourth inning, Aaron stepped up to the plate with Scully behind the mic to describe a drama that would resonate far beyond the ballpark. “It’s a high drive into deep left-center field. Buckner goes back to the fence. It is gone!” Scully said, then let the crowd take the mic for 26 jubilant seconds before remarking on Aaron’s historic achievement: “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

A dozen years later, Bill Buckner, the outfielder who watched Aaron’s recordbreaking home run sail just out of reach, would be at the infamous heart of another one of Scully’s most memorable calls. Now playing first base for the Boston Red Sox, Buckner and his teammates faced the New York Mets in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. They were up two runs and only one out away from breaking the so-called Curse of the Bambino, having not won a World Series since trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees after the 1919 season. But the Mets staged a gritty comeback to tie the game in the 10th inning. Finally, the Mets’ Mookie Wilson hit a seemingly simple ground ball Buckner’s way. “Little roller up along first, behind the bag, it gets through Buckner!” Scully said, his voice rising. “Here comes Knight, and the Mets win it!” Once again, he let the crowd roar—this time for nearly two minutes, as viewers were shown the replay of Buckner’s error, a delirious New York crowd, the jubilant Mets, and the despondent Red Sox. “If one picture is worth a thousand words,” Scully said when he returned to the mic, “you have seen about a million.”

The ‘Patron Saint of WFUV Sports’

Scully’s iconic style made him an inspiration for generations of sports broadcasters who followed in his footsteps at WFUV and at Fordham, including Michael Kay, FCRH ’82, the voice of the Yankees for the YES Network, who called Scully “the greatest broadcaster who ever lived.”

“Every game was a master’s class as he turned an inning into poetry. And as great as he was, he was just as nice. Class, elegance, and grace were all part of his humble but regal being,” Kay wrote. “His loss is heartbreaking as his golden voice is silenced, but he will live forever as an example of what to try and be on and off mic. RIP Mr. Scully, and rest easy knowing how much you made a difference to all who met you and had the joy of listening to you.”

In the 2020 documentary on WFUV sports, Hall of Fame basketball broadcaster Mike Breen, FCRH ’83, described what made Scully the best: “His vocabulary, his storytelling, his personality—everything. He just was perfect,” Breen said. “It made you … [want] to make sure you were always prepared anytime you went on the air.”

Bob Ahrens, WFUV’s sports director for 20 years before his retirement in 2017, said Scully always made time for the students. They usually interviewed him about once a year for the weekly One on One call-in show, and Ahrens said Scully hosted at least two workshops over the phone. “They can’t see him in person, and the control room is packed,” Ahrens said. “He loved FUV, he loved Fordham, and he was always willing to help out.”

In 2008, he became the first recipient of WFUV’s Vin Scully Award for Excellence in Sports Broadcasting, a lifetime achievement award that Breen accepted last fall and Kay took home in 2018. “To be given an award with Vin Scully’s name on it is beyond anything I could have ever imagined,” Kay said at the awards ceremony. “He is the patron saint of WFUV sports, he is the patron saint of anybody who does baseball play-by-play. He is the best at what he’s done.”

Mike Watts, GABELLI ’14, who calls games for ESPN, Westwood One, and other networks, said that Scully inspired him to come to Fordham. “There is no WFUV sports without Vin Scully,” Watts said. “His name gave all of us credibility. To have the greatest at anything come from your school, your radio station, your program—it’s the light that all of us were following.”

‘Smile Because It Happened’

On October 2, 2016, Scully called his final game. Before heading to the playoffs, the Dodgers and the Giants—two teams with New York roots—concluded the regular season with a game in San Francisco. In the final inning, Scully said that he’d had a line in his head all year, a common, anonymous expression often mistakenly attributed to Dr. Seuss, he said. “The line is, ‘Don’t be sad that it’s over. Smile because it happened.’ And that’s really the way I feel about this remarkable opportunity I was given, and I was allowed to keep for all these years. … I have said enough for a lifetime, and for the last time, I wish you all a very pleasant good afternoon.”

—Kelly Prinz, FCRH ’15, is an associate editor of this magazine. Chris Gosier and Ryan Stellabotte contributed to this article.