He goes on: “I’m going to tell you what the right answers should have been, and you will take the test again,” he says of the deliberately tough exam, laughing gently. A student raises her hand. “Should I step out? Because I missed it and I’ll be making it up?”

“No, don’t,” says Mankoff, who joined Esquire magazine last spring after two decades as the cartoon editor at The New Yorker. “For you, I’ll make a completely different exam—with the same questions but a different font.”

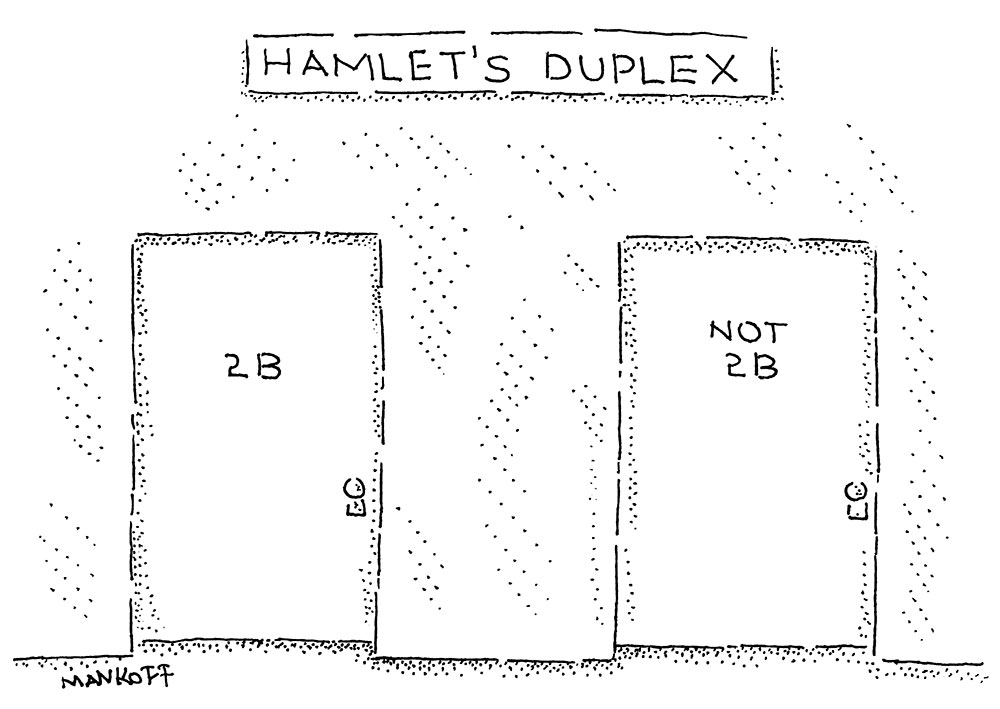

Last fall at Fordham, Mankoff taught Humor as Communication, a course that allowed him to draw not only on his experiences as a longtime practitioner of the art (he sold his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1977) but also on his deep knowledge and curiosity about what makes something funny.

Last fall at Fordham, Mankoff taught Humor as Communication, a course that allowed him to draw not only on his experiences as a longtime practitioner of the art (he sold his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1977) but also on his deep knowledge and curiosity about what makes something funny.

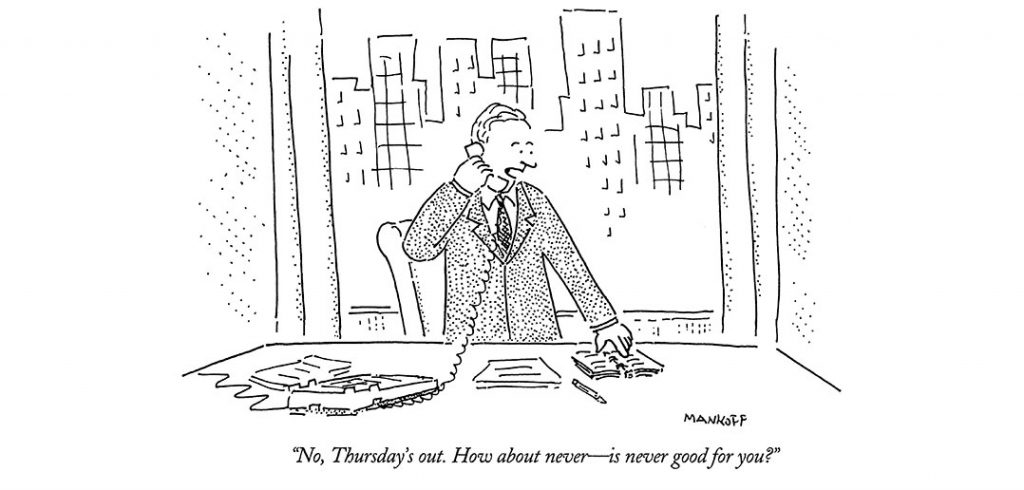

During the early 1970s, he began pursuing a doctorate in experimental psychology. “When, after two years in the program, my experimental animal died (and not from laughter, I might add), I took it as an omen to quit,” he wrote in his charming 2014 memoir, How About Never—Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons.

But in the past decade, he redeveloped an interest in the subject. “I discovered that the field I’d abandoned could help me better understand the field I was in, and vice versa.”

But in the past decade, he redeveloped an interest in the subject. “I discovered that the field I’d abandoned could help me better understand the field I was in, and vice versa.”

In the classroom, Mankoff mixed entertainment with academia, bringing in guest lecturers like Laura Little, a professor at Temple University law school and the author of the forthcoming book Guilty Pleasures: Comedy and Law in America. He also encouraged his 30-odd students to consider the social psychology of humor, how it “unites and divides, teaches and taunts, attracts and repels,” he says. What are the consequences of racist and sexist humor? What kind of jokes can be made, and who can make them?

“The idea is for everybody in the class to have the idea that humor is this interesting topic, that it’s complicated,” he says. “I want them to take away an experience that will inspire their curiosity and get them to question their attitudes. I think that’s a really interesting discussion to have. And it’s in line with this Fordham idea of doing good in the world.

“Humor can be used as a force for good or evil,” Mankoff adds. “I’ve chosen evil, but that’s just me.”

Mankoff in Conversation with Jim Jennewein

Early last fall, Bob Mankoff sat down with screenwriter and Fordham lecturer Jim Jennewein to talk about cartoons, the history of stand-up comedy, and comedians delivering hard news.

Jim Jennewein: Tell us about your course.

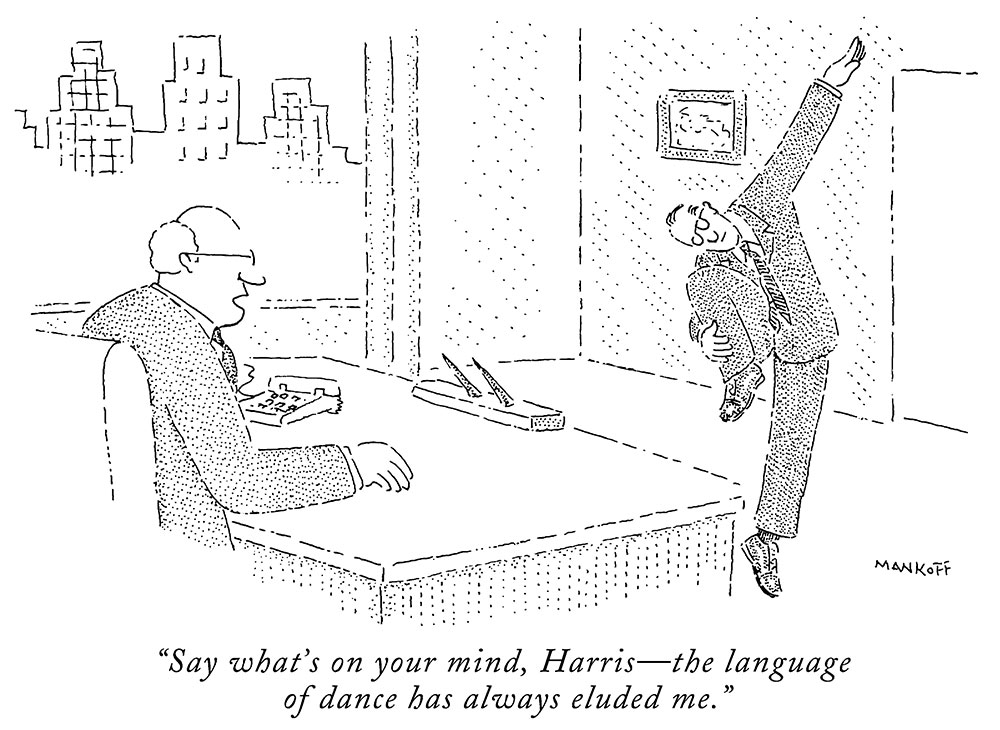

Bob Mankoff: We’re exploring this idea of how we all use humor, not just for entertainment but to communicate in personal relationships, in advertising, in persuasion, in all the ways we use humor in addition to entertainment. I think that’s actually the most important part of humor.

Jim: So, humor is a communication tool?

Bob: Sometimes humor is used to say things we ordinarily couldn’t say. Because in humor we can say, “Hey, I was only joking!” Often people have different agendas. You don’t know the other person’s agenda, and they don’t know yours. So, one part of humor is social probing. Are you playful? Is your mind flexible? If you tell a joke on a certain topic, I can tell pretty quickly if you are liberal or conservative by who you’re making fun of. So there are all these dynamics that go into the use of humor in life and in communication.

Jim: Has stand-up created a new lexicon in comedy?

Bob: Yes, it has. And it’s one of our strongest forces now in comedy: standup as a means of communication, as a means of expression, and as an art form. The history of stand-up probably comes from [monologues that were done in]vaudeville.

Jim: There were ethnic comics in vaudeville who did accents of the immigrant classes.

Bob: Oh yeah, there was all of that. This is terrible, but I have to say there was the Jew routine: the hebe; the Irish routine: the mick; and Italian: the wop. These are all obviously ethnic insults. But that’s what these routines were called. And there were worse that I won’t go into, but it was partly a heterogeneous society’s way of dealing with its own immigrant conflicts rather than killing each other. Epithets aren’t good, but they are much preferable to extermination.

Bob: Oh yeah, there was all of that. This is terrible, but I have to say there was the Jew routine: the hebe; the Irish routine: the mick; and Italian: the wop. These are all obviously ethnic insults. But that’s what these routines were called. And there were worse that I won’t go into, but it was partly a heterogeneous society’s way of dealing with its own immigrant conflicts rather than killing each other. Epithets aren’t good, but they are much preferable to extermination.

Jim: Right, it was a way to process the dissonances and the conflicts of having a hundred different ethnicities in one city or in one country.

Bob: One of the classes I’d like to teach somewhere is just called the History of Comedy, the comedic thread that goes from Greece to Rome to commedia dell’arte to music hall to vaudeville, and as you see all of its forms, [you realize that]a lot of the routines go back a humor have changed in that we want to feel more participatory. You know, in vaudeville, in Henny Youngman’s “Take my wife—please” routine, you’re not really participating.

Jim: You’re letting the jokes wash over you.

Bob: And he took that form to its extreme, like, “I’ve got an encyclopedia of jokes. Just sit back—if you don’t like one, I’ll give you another, and another.”

Jim: And we knew that the persona was a construct.

Bob: Right, right. We knew none of it was true. But there has been an evolution of the form, and what I say about cartoons is true about everything, I think, and it’s that quality comes out of quantity. Is most stand-up comedy good? No. Is some stand-up great? Yes. Because of the huge number of people who do it, the heterogeneity of the groups who do it. Originally it was sort of a Jewish and Irish tradition. Back in 1979 a study found that 80 percent of the people in professional comedy in the United States were Jewish—80 percent . Now I think it’s actually one of the gifts that Jews gave to the world. Besides persistent anxiety.

Bob: Right, right. We knew none of it was true. But there has been an evolution of the form, and what I say about cartoons is true about everything, I think, and it’s that quality comes out of quantity. Is most stand-up comedy good? No. Is some stand-up great? Yes. Because of the huge number of people who do it, the heterogeneity of the groups who do it. Originally it was sort of a Jewish and Irish tradition. Back in 1979 a study found that 80 percent of the people in professional comedy in the United States were Jewish—80 percent . Now I think it’s actually one of the gifts that Jews gave to the world. Besides persistent anxiety.

Jim: We’ve become increasingly reliant on comedians to deliver very serious truths, like what’s happening in the news. What are your thoughts on that?

Bob: We now have people getting serious content through comedy: Jon Stewart, and now John Oliver, Stephen Colbert, Trevor Noah. And, you know, that is definitely a real shift, but it goes back a little ways. There was Mark Twain and Will Rogers, for example. What we have now is humor as a kind of rhetoric. And to some extent the politicians are doing the work for you, because you have them on video contradicting themselves.

But what this means is that humor has become part of the armamentarium of argument. And this is where we come to persuasion and the question of how much does it persuade? In the end, I think you can only really persuade through real argument, although humor can be a way in to let you do that.

But what this means is that humor has become part of the armamentarium of argument. And this is where we come to persuasion and the question of how much does it persuade? In the end, I think you can only really persuade through real argument, although humor can be a way in to let you do that.

The default condition in life is seriousness. Serious argument, logical argument, that’s how we have to live our lives. Humor is the icing on the cake. And the truth is, cakes without icing are lousy.

Watch a video of Mankoff in conversation with Jennewein