“I did it because I liked the feel of it,” he says. “There was something about having a camera that made me think, made me feel more alert and more aware of my environment.”

Few days made Racioppo feel more alert than Halloween.

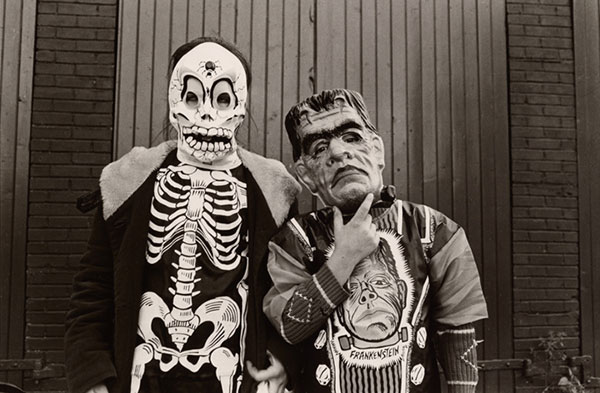

As a kid, he’d go trick-or-treating with cousins and friends, and they’d have make-believe fights with shaving cream and “chalk bags”—old socks filled with pieces of chalk crushed to dust. By nightfall, they’d head indoors to bob for apples, carve jack-o’-lanterns, and enjoy the sweet loot they’d foraged from friendly neighbors. “I loved the activity, the crazy costumes, the theatricality of it,” he says.

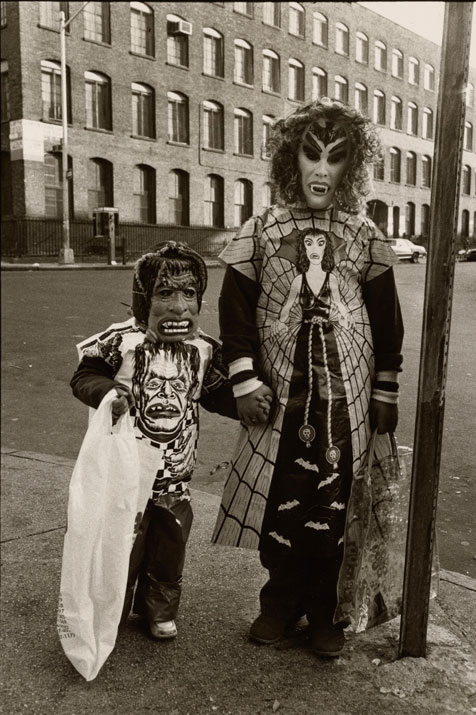

By the mid-’70s, he was in his 20s, a recent Fordham graduate working at a high-end Manhattan photo studio. He’d long since stopped trick-or-treating, but the spirit of the holiday still called to him.

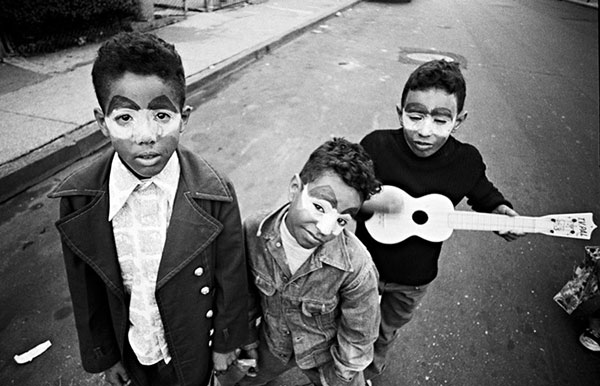

“I started leaving work early on Halloween to get back to Brooklyn. I photographed kids from 3 o’clock, when they got out of school, until it got too dark to shoot with available light,” he says, noting that he’d start near Park Slope and wander south to Sunset Park. “That first year, I came out of my house and the kids charged me—they ran up to me full speed for me to take their picture.”

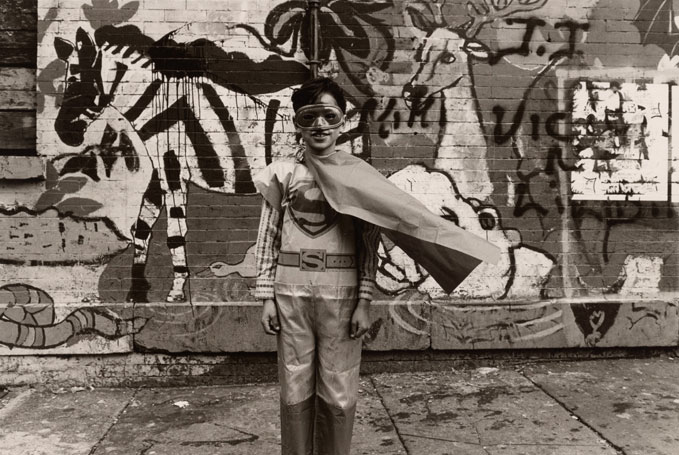

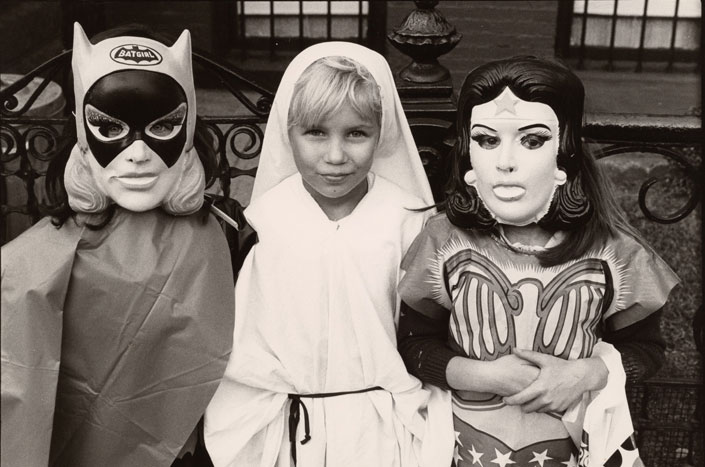

“It became a yearly thing,” he says, “so from ’74 to ’78, I had all these fabulous photographs. And the kids and costumes were terrific. There’s the classics—the ghosts, vampires, angels. And every year there’s a movie that’s the big movie. One year it’s Planet of the Apes, then it’s Jaws, then Star Wars, and sometimes those cultural costumes would linger a year or two. But they have a shelf life—I mean, when you look back and see the Fonz costumes. These days, who even knows who the Fonz was?”

Ever since 1974, Racioppo says he’s had an easy rapport with the neighborhood kids, who took to calling him “Picture Man,” a nickname he says he took as a great compliment.

In October 1979, the Village Voice featured eight of Racioppo’s Halloween images, and the following year, Scribner’s published Halloween, his first book.

“That was really my first notch up,” he says, noting that it helped launch his decades-long career in photography. From the late 1980s until 2011, he was a staff photographer for the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, and he has earned several grants, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, for his own work documenting the urban landscape.

“Part of what I do is about stuff disappearing,” he once told The New York Times. That’s an explicit theme of his latest book, Brooklyn Before: Photographs, 1971–1983, published last month by Cornell University Press.

The book highlights working-class families—most of them Italian American, Irish American, and Puerto Rican—as they go about their daily lives, celebrating Catholic sacraments and holidays, playing stickball and congas on the sidewalk, hanging out on stoops and fire escapes, posing with boom boxes in front of graffiti-tagged walls, and taking part in patriotic parades and religious processions.

“I did not know it at the time, but I was recording a part of Brooklyn that would soon be remade by gentrification,” Racioppo writes in the book’s preface. “Slowly but surely, the residential ‘gold rush’ expanded south from Park Slope … toward Green-Wood Cemetery,” driving up rents and home prices, and driving out many working-class families.

Brooklyn Before features a handful of the Halloween photos that helped launch Racioppo’s career. Today, he lives in the Rockaways, where he has continued photographing trick-or-treaters on Halloween. This year, however, he says he may head back to Brooklyn to meet up with his grandsons in Park Slope, where, although the times have changed, the spirit of the holiday is still strong.

“They’re 8 and 6 years old now. They won’t just get a chalk bag and run around till dark by themselves. They’ll go to supervised play or an after-school Halloween celebration,” he says, like the annual children’s parade. “Halloween is always fun. There are so many great things about it.”