At the Louis Calder Center, scientists explore ecological mysteries and study society’s impact on the natural world.

To the casual observer, Fordham’s Louis Calder Center might seem to be just another quiet tract of Hudson River Valley forest. But for natural scientists, it abounds with opportunity. Explore the 113-acre biological field station in Armonk, New York, and you’ll find a bounty of ecosystems and animals, from the four-legged to the microscopic. At the heart of the preserve is a 10-acre temperate lake teeming with a diversity of aquatic life. Go high enough and, way off in the distance, you can see another big player in the preserve’s ecology: New York City, which begins only 16 miles away.

Its proximity has never been more relevant. “Humans and our cities are the most dominant forces of contemporary evolution now,” says Jason Munshi-South, Ph.D., a Calder-based biology professor who recently co-authored a paper in the journal Science on how species are evolving within cities. Other scientists at Calder study invasive species that arrive via big-city commerce. And they tackle many other mysteries: why some animals survive new threats while others don’t, how nutrients flow beneath the soil, or how insects transmit disease.

The center was born 50 years ago when the land was given to Fordham by the Louis Calder Foundation, named for the paper and pulp magnate who maintained a summer home on the property. Today, that home is Calder Hall, one of several buildings in which students and professors analyze DNA samples, inspect plant and animal specimens, hold classes, and generate knowledge.

Among many other public services, the Calder Center supports the nation’s longest-running study of ticks and Lyme disease, and its scientists work to illuminate society’s impact on nature at a time of growing concern about biodiversity and climate change.

It is also a crucial training ground: “The most important thing we do here is make scientists,” says Thomas Daniels, Ph.D., an expert in tick- and mosquito-borne diseases who has served as the center’s director since 2014.

On a sparkling autumn day late last October, FORDHAM magazine tagged along as undergraduates, graduate students, professors, and visiting scientists went about their work—gently probing, collecting samples, and explaining the science behind their work and its potential impact.

Evolution in the Big City

In recent years, Fordham biologist Jason Munshi-South, Ph.D., and his team of graduate and undergraduate students have become known for their studies of urban wildlife and pest species, most notably rats.

“The initial idea was to understand what a New York City rat is, from all ecological and evolutionary angles,” he says of one project, which grew to a global scale and has public health implications. “We’re using DNA to understand how they move around the city and how they’re related to other rat populations.”

In a first-floor lab in Calder Hall, doctoral student Carol Henger uses similar methods to study coyotes, animals that only recently moved into the city for the first time, Munshi-South says. She’s looking at DNA markers from coyote scat collected in Pelham Bay Park and elsewhere to infer how individual coyotes are related, what they’re eating, and how they’re dispersing.

Meanwhile, Nicole Fusco, another doctoral student in Munshi-South’s lab, sequences DNA to study gene flow among populations of salamanders.

Biodiversity and Climate Change

In the Calder Center’s Lord & Burnham greenhouse, constructed on the property nearly a century ago, doctoral student Stephen Kutos has been growing pairs of potted trees and studying how they pass water and nutrients back and forth via subsoil networks of fungus.

“Tree stumps have been found that are still alive hundreds of years after the tree was cut down, quite possibly because surrounding trees send them nutrients,” he says. With further study, he adds, it may be possible to restore the wild population of one type of tree he’s growing, the American chestnut, which was eradicated from the wild 100 years ago by blight.

Restoring the tree could help combat climate change, scientists believe, because the American chestnut can absorb and store carbon quickly.

In an adjacent greenhouse, several researchers work on an evolutionary study initiated by Fordham biologist Steven Franks, Ph.D., and focused on Brassica rapa (field mustard). As Franks demonstrated in an earlier study, the annual plant evolved earlier flowering within just five years to cope with drought conditions in California.

The Mystery of the Red-Backed Salamander’s Survival

Late in the morning, undergrads Dan Khieninson and Erin Carter and doctoral student Elle Barnes enter Calder forest in search of red-backed salamanders.

“You can find them anywhere in the forest as long as the soil’s moist,” Barnes says before the group navigates a steep decline to the forest floor.

She indicates several flat, weathered pieces of wood she’s left behind. “You’re more likely to find them under here.” The three researchers crouch down and soon locate several specimens.

They’re trying to discover why red-backed salamanders are not affected by the chytrid fungus that is devastating other amphibian populations.

“It’s not enough to just study the ones that are going extinct,” Barnes says. “There are solutions in the ones that will survive. What do they have that other amphibians are lacking?”

The answer lies in their microbiome, Barnes says. She, Carter, and Khieninson use cotton swabs on the salamanders’ bodies to collect samples of microorganisms that they can test against chytrid fungus in the lab. The impact of their research could extend beyond conservation biology, Barnes says: “The discoveries we make about disease and microbiomes can be applied to multiple systems, including humans’.”

A Closer Look at a Ubiquitious, Ecologically Valuable Species

Michael Kausch, a doctoral student in aquatic ecology, rows a boat out on Calder Lake to take some water samples he can later test for cyanobacteria at the lakefront McCarthy Laboratories. Meanwhile, inside the lab, his fellow doctoral student Stephen Gottschalk is working with their Fordham supervisor, John Wehr, Ph.D. Gottschalk is studying green algae in the Characeae family.

“They’re an important food source for birds, a habitat for insects, and they support fisheries,” he says.

So far Gottschalk has collected samples in nine U.S. states, and he’s been working at the New York Botanical Garden under the supervision of Kenneth Karol, Ph.D., to examine his samples on a molecular level.

He’s finding that what scientists once thought were just subtle differences among green algae are in fact ecologically important distinctions. “They’re designated as one species,” Gottschalk says, “but what it looks like to me so far is these are very regionally distinct.”

Mosquitoes, Ticks, and the Pathogens They Carry

Insect-borne diseases are a big part of the research focus at Routh House, the vector ecology lab at the Calder Center that’s jointly run by Fordham and the New York state health department. Inside the lab, scientists study samples of various species, such as the aggressive and potentially disease-carrying Asian tiger mosquito. Outside, they collect specimens and conduct surveillance projects.

“We set up mosquito traps all around the lower Hudson Valley,” says Marly Katz, a state employee and Fordham doctoral student. “All the mosquitoes end up here, where I identify them, and then we send a bunch [to the state health department]for disease testing.” She and her colleagues are also collaborating with Columbia University scientists to “map the Asian tiger mosquito,” she says, and determine if changes in climate are affecting its migration patterns.

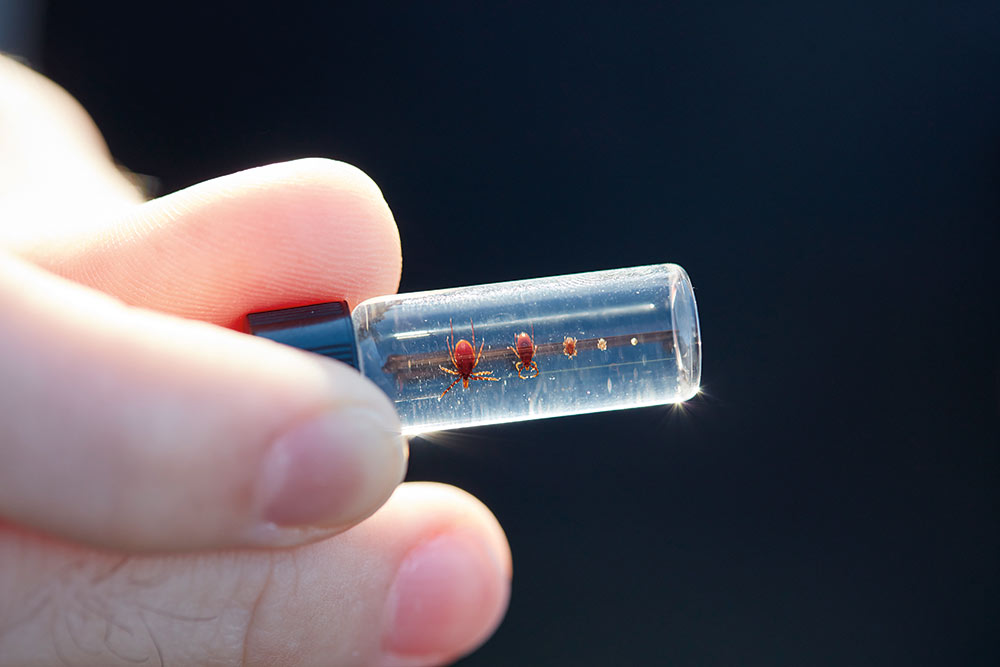

While Katz checks a mosquito trap, research technician Richard Rizzitello collects ticks by dragging a white cloth across the ground and then pulling them off with forceps (he uses a lint roller to collect any larvae).

One Calder scientist, Nicholas Piedmonte, displays egg-to-adult samples of the blacklegged tick, which can carry the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.

“These are great for education and outreach,” he says, particularly in central New York, “where ticks are kind of a new problem.”

View a timeline of the Calder Center’s history. And watch a July 2017 video celebrating the center’s recent golden anniversary.