There was a stark moment at the Human Rights Day celebration held on Dec. 14 at the Pope Auditorium, as a student from the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) approached the podium.

“My father spit in my face,” she said.

Another woman testified that her husband held her baby under one arm while beating her with his free hand.

Several colleagues stood behind the speakers. They wore purple, the color of domestic violence awareness. Each testified. Some wept. All were students at the GSS, which sponsored the event.

In another section of the auditorium, students presented research posters that ranged from harm reduction to veterans’ rights. But what rose from behind the numbers were portraits of survivors.

“Yes, there are numbers, and yes, there are statistics, but I wanted to show that I’m the face behind the numbers,” said Hope Ghazala, a social work masters student and a case manager at Safe Horizons, a domestic violence center.

Ghazala’s father abused her as a child. She said that as an adult she sought out a similar relationship with her boyfriend. She said that her experience made her want to break the cycle and help others. She was not alone. Many social work students experience firsthand the pain of their clients. And yet the cold numbers of student research belie the highly emotional connections.

“There’s a sense of distance with the data, but sometimes social workers need to protect themselves through that,” said Ghazala.

Ghazala said, and several of her colleagues agreed, that while the data are needed to change policy, testimonials bring it home.

“People need to know that one in six women is abused. And that abuse can be economical, emotional, or physical. But how do you fill in that gap between the data and person?” she said.

Loren Bahor worked with Laura Berman and Johnnie Alexander on comparing harm reduction policies to outright prohibition policies. All clearly came down on the side of harm reduction, which promotes outreach to drug abusers rather than incarceration.

Berman said that her personal research focuses on how political back room deals effect policy. Alexander’s work focuses on how policing and drug policy promote racial profiling of African American males. Bahor’s work focuses on the effects of substance abuse on the Native American community. It fell to Alexander to merge the three diverse specialties into a cohesive whole. He found that harm reduction provided a common denominator.

“The ‘War on Drugs’ fails when it comes to treatment. It’s too focused on the big picture and not the individual,” said Alexander.

“As social workers, we focus on individuals.”

Alexander said he has seen first hand how policing and drug policies foster “racial predispositions.” Bahor is not Native American, but said she could see parallels with the communities in Alexander’s research.

Tina Maschi, Ph.D., professor and director of the Be the Evidence Project, one of the event sponsors, said that related life experiences are not necessary.

“There’s always a way of engagement, the concept is to find something you’re passionate about,” she said. “Sometimes the students have lived the experience, and helping others is part of their own personal growth.”

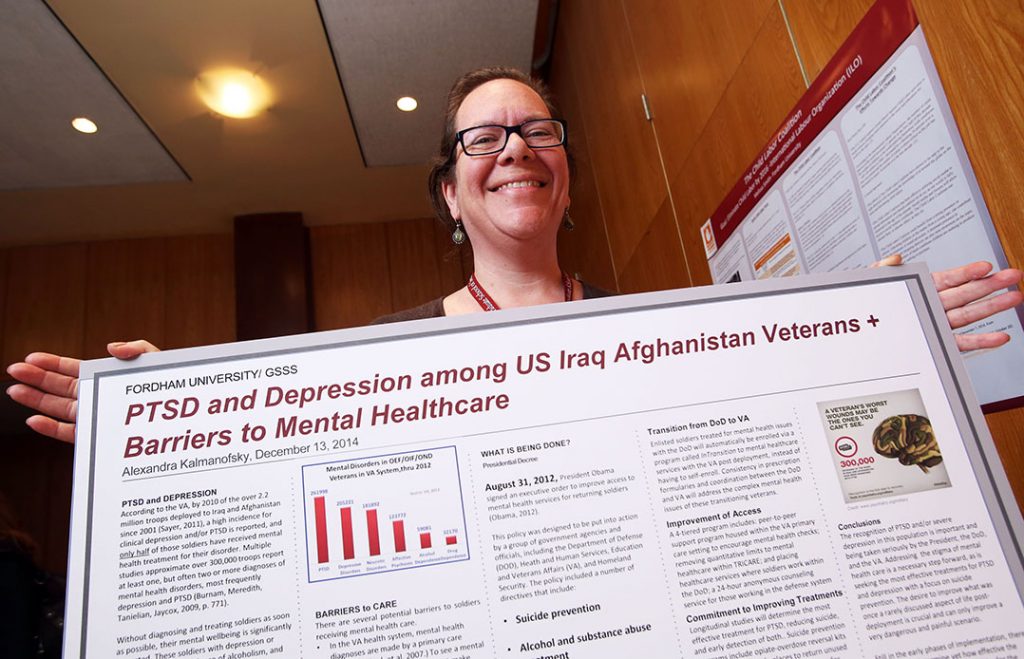

Alex Kalmanofsky represented the dichotomy better than most. Kalmanofsky studies post traumatic stress disorder and depression of veterans who have fought in the Iraqi and Afghanistan wars. She said that of the 300,000 returning veterans, only half sought mental health services.

“I’m a lefty liberal with a federal record for protesting war, and I fight for veterans’ rights,” she said.

“There’s a significant difference between the soldier and the war.”