And, on top of it all, a sense of alienation.

These are just a handful of reasons why it’s difficult for colleges and universities to retain students of color in the STEM fields, says Jennie Park-Taylor, an associate professor in the Graduate School of Education.

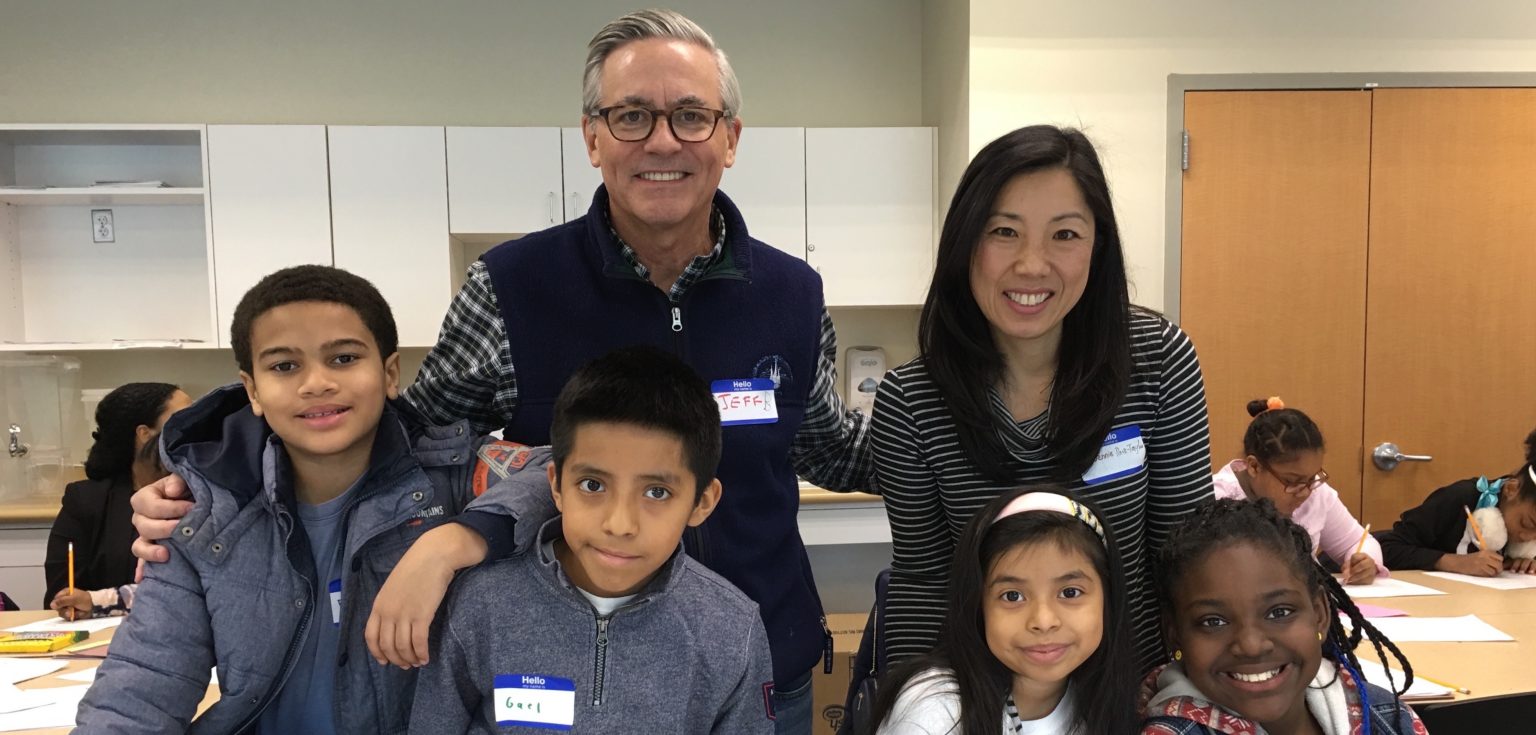

Last year, Park-Taylor and her research team began conducting a pilot project on urban minority youth and young adults and their engagement in STEM education. They’re trying to pinpoint why so many underrepresented minority students drop out of STEM majors and identify possible points of intervention.

Researchers have already addressed the issue from a quantitative lens: dropout data, student enrollment numbers, retention rates. Nationwide, 71 percent of Latino students intending to earn a STEM degree fail to complete their program within six years, according to a study out of UCLA. For black students, the non-completion rate is even higher—78.2 percent. Another study in the journal Plos One says that women of any race are 1.5 times more likely to leave the STEM pipeline after taking Calculus I in college, compared to men.

But few researchers have ventured past the numbers. Park-Taylor and her team are doing something different—searching for the answers through the students’ personal narratives. They’re in the midst of interviewing middle school students, high school students, and college undergraduates in the Bronx about their personal experiences with STEM education. Their questions focus on three areas: STEM preparation; persistence—what keeps them going, what happens when they fail or succeed, who supports them; and the ways they gain access to STEM careers and opportunities.

“How prepared do they feel in math and science to go on to the next level? What kind of access do they have to the advanced science and math classes in their schools?” said Park-Taylor. “And once they’re there, how do they succeed? What makes it harder for them?”

They speak on a one-on-one basis in-person, via Skype, or by phone. Some interviews take as little as 25 minutes; others last for more than an hour and a half. So far, Park-Taylor’s team has spoken to more than 30 students. There are three young women who stand out in her memory.

The first is a woman of color attending a prestigious, predominantly white college in the Boston area. She had excelled in math and science until middle school, when she struggled with science and lost her confidence. She is now a political science major who wants to be a lawyer. Several of her friends, students of color who were in STEM majors (many of them women), recalled math and science professors who would tell their students on the first day of class, “Half of you won’t pass. Half of you are going to change your major. If you’re not serious about this class, I would leave right now.” Even after going to office hours for extra help, they were further discouraged. Professors would suggest that they change their major to, for example, English or African Studies. All of them, the student said, changed their majors by the time they were seniors.

Another interviewee was a straight-A student in her high school math and science classes. As a first-year college student engineering major in college, she took advanced calculus and chemistry. She started getting Cs.

Her professor, said Park-Taylor, told the student, “I’m not sure I want someone who’s getting a C to build my bridge in the future.” Many of her male classmates made study groups, but turned their backs toward her and the girl sitting next to her. At the beginning of her chemistry class, she said, there were other girls in the class. By the time the midterm rolled around, she was the only one left.

“Teachers that create unfriendly environments have an enormous negative impact on students,” said Park-Taylor. “And not just students’ motivation, but their sense of self-efficacy, belongingness, and eventually interest in a field that they may have been really passionate about.”

And the grading system in math and science classes doesn’t help either, she added. Many courses have two major exams: the midterm and final. On the other hand, English and literature classes have multiple papers.

“There are opportunities to improve your grade, little by little, versus these high-stakes exams that happen in the middle and the end,” said Park-Taylor. “It’s a make-or-break situation for students.”

But not all the stories were negative. Park-Taylor recalled a sixth-grade girl who felt motivated in math. She scored a “high 2” on her state exam—just short of a 3, the benchmark for achieving grade level. On the first day of school, the principal praised the students who scored 3 or higher. And he also included that sixth grader—in fact, all the students who scored a high 2.

“She did not have a 3 on her exam,” said Park-Taylor. “But she knew she could because the principal told her.”

So far, Park-Taylor’s team has found two key takeaways: The power of peer support, parents, mentors, and community-based activities on academic success should not be underestimated, and engaging teachers make a positive difference in their students’ lives (and the converse is also true).

This pilot study is currently funded by a $10,000 proof-of-concept grant from the office of Virginia Roach, Ed.D., the dean of the Graduate School of Education, but Park-Taylor also plans on applying for bigger grants to conduct research on a larger scale. For now, she’s planning on submitting some of her research for publication by this December. She hopes her team’s results will find their way into intervention practices, college student advising, and other student programs. And, perhaps most importantly, she hopes they fuel change.

“What if [professors] said, ‘My job is to make sure everyone in this class succeeds. I’m gonna do everything I can in my power to make sure you understand this material. I have GAs or TAs to support you. I’m gonna have office hours,” Park-Taylor said. “I want you to know you belong here. You may not feel like it because you don’t see a lot of people that look like you, but you belong here. I wonder what that would be like.”