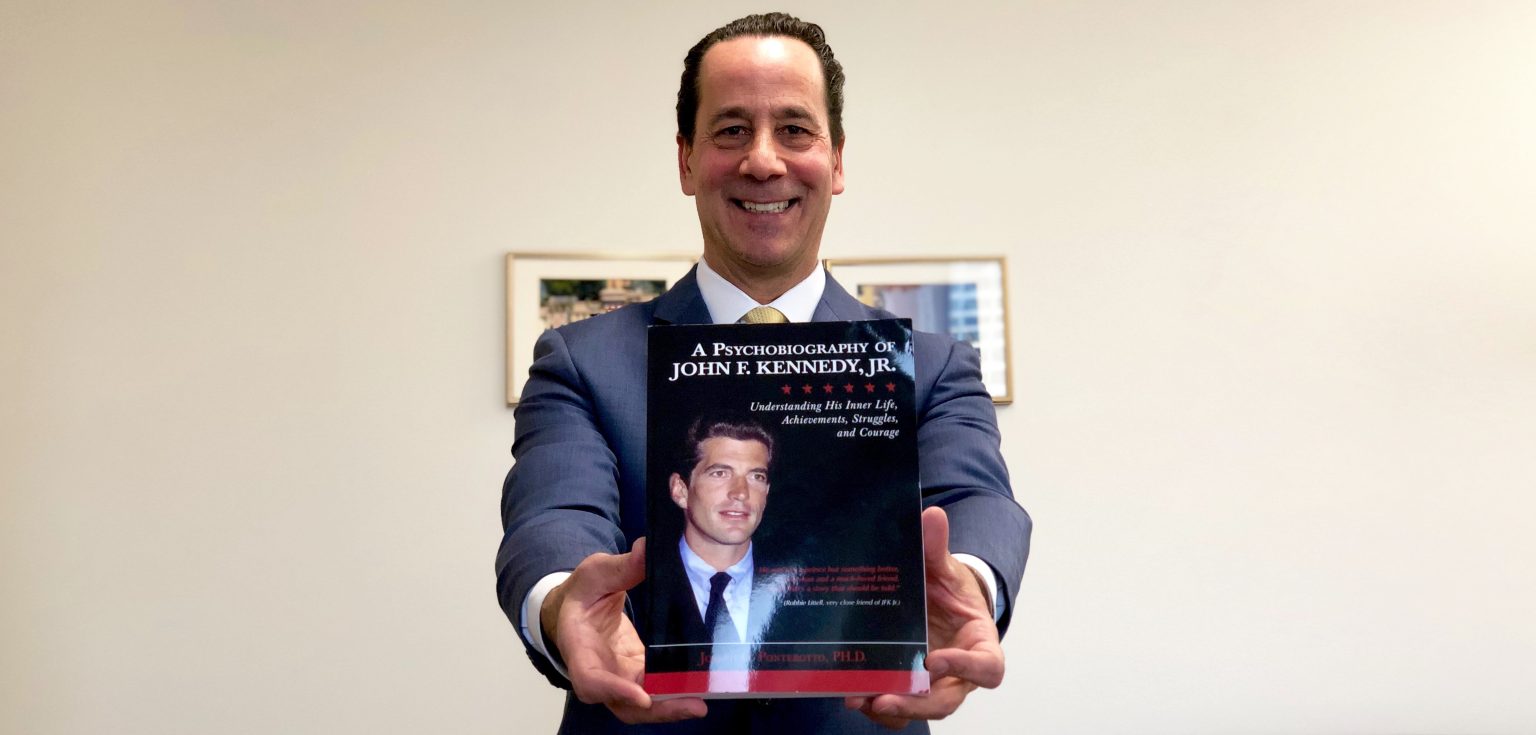

In his new book, “A Psychobiography of John F. Kennedy, Jr.: Understanding His Inner Life, Achievements, Struggles, and Courage,” Fordham professor and clinician Joseph G. Ponterotto, Ph.D., uses psychology to unravel who Kennedy was—and who he could have become, had he not died 20 years ago in a fatal plane crash at age 38.

Unlike a biography, a psychobiography tries to explain a person’s psychological makeup, personality, and life, using psychological research and theories, explained Ponterotto, who teaches in the Graduate School of Education.

Ponterotto illustrated the difference between the two genres with a photo of an iceberg. A small block of ice bobs above the waves. The rest—a huge, monolithic hunk of ice—is hidden beneath the surface.

“What’s above the water is usually what a biographer studies. That’s what people see—a person’s status and achievements,” he explained. “The psychobiographer is more interested in what led to that: the person’s inner drives, feelings, and experiences.”

At first, Ponterotto’s friends and family were puzzled by his decision to profile the junior Kennedy. “Some said, ‘You mean the president?’” he recalled. “I said, ‘No, no. There’s a lot written about the president, but we don’t know [as much]about his son.”

Ponterotto begins the book with the public’s perception of Kennedy Jr. He had surveyed 75 adults in the New York City area on what they knew about Kennedy Jr. and what they wondered about him.

“What were his private and public views on major issues of today: immigration, police brutality, globalization, discrimination, LGBTQ rights?” one survey participant asked. “Was he able to do what he most wanted in life?” inquired another.

The 212-page book also includes a comparison of Kennedy Jr.’s personality profile to U.S. presidents like Ronald Reagan; a psychological analysis related to the early loss of his father and relationship with his mother, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis; and a chapter that explores a question harbored by many: Would Kennedy Jr. have followed in his famous family’s footsteps and pursued a career in politics?

“Could he have run in 2016 against Donald Trump, rather than Hillary Clinton?” Ponterotto asked. “How would the country be different if he were alive?”

Ponterotto based his psychobiography on nearly 100 sources: letters, speeches, poems, and recorded radio and television interviews by Kennedy Jr.; memoirs, diaries, and autobiographies penned by people who had been close to him; in-person, phone, and email interviews with Kennedy Jr.’s colleagues and experts; and additional third-person documents.

An included excerpt from a book by Kennedy Jr.’s good friend Robbie Littell touched on what the young Kennedy was like while attending Brown. Despite attending functions on weekends with leading politicians and businessmen, Littell wrote, Kennedy Jr. never talked about them when he returned to campus, likely because he didn’t want to be seen as a public figure. “It was as though he deliberately split himself in two.”

What Ponterotto found most surprising about Kennedy Jr., he said, was his social and emotional intelligence. He had failed the New York bar exam on his first two tries. But he was a man who could read people well—a person who could put people at ease, despite his wealth and fame.

“He was able to bring people together—very different folks. He had his college buddies, rugby friends, pilot friends, [etc.]. He was able to bring them together to reach common goals in terms of working on [George] magazine, the foundations that he started, reaching up to help folks who work with disabled individuals, helping them with training and education,” Ponterotto said.

The psychobiography also delves into Kennedy’s thoughts during his final moments—his mental well-being and the fatal choices that would lead to not only his death, but also those of his wife, Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and her sister Lauren Bessette in a 1999 plane crash. To get a better sense of what had happened, Ponterotto interviewed two experienced small aircraft pilots who had flown above the area where Kennedy crashed his single-engine plane. He also obtained the official accident report through a Freedom of Information Act request.

Ponterotto acknowledges that the book’s content could be emotionally sensitive to Kennedy Jr.’s family and friends. While he was writing it, he considered how the Kennedy family—his sister, cousins, and godchildren—might react. In the last chapter, he says that given how much has been written about JFK Jr., coupled with the family’s requests for privacy, he did not feel comfortable seeking their consent for the project. But he did obtain consent from all sources he interviewed, and he double-checked the accuracy of his reporting.

“Psychologists are going deeper than historians or journalists,” Ponterotto explained. “They’re dealing with a deeper level of emotionality, a higher bar of ethical protection.”

This is Ponterotto’s 14th published book and his second psychobiography. In 2012, he profiled Bobby Fischer, the youngest chess grandmaster in the world, in a psychobiography that brought his name to the big screen. Ponterotto was also the historical consultant for the 2014 major motion picture Pawn Sacrifice, a biographical drama about Fischer that starred Tobey Maguire and Peter Sarsgaard.

The psychobiography was published last November by Charles C. Thomas, Publisher LTD. But Ponterotto explained that the book’s copyright date is 2019, in honor of the 20th anniversary of JFK Jr.’s death.

If he could meet the man he studied for four years, said Ponterotto, he’d like to have a beer or soda with him, or perhaps play a game of touch football in Central Park. They could speak as members of the same generation. Their families both immigrated to the U.S. during the same period—the Kennedy family is from Ireland, the Ponterotto family is from Italy—and the two men share a two-year age difference.

“I’d want to get to know him as a friend,” Ponterotto said. “Not as a Kennedy.”