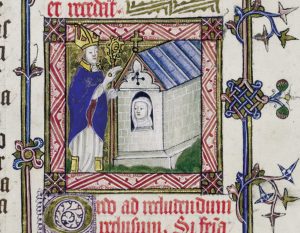

To earn a master’s degree in medieval studies, Grissom, who uses they/them pronouns, devoted their master’s thesis to exploring the lives of anchorites, members of a Christian Monastic tradition primarily practiced by women from the 11th to the 16th century.

Anchorites voluntarily confined themselves to a tiny, windowless room attached to a church for the rest of their lives. The community supplied them with sustenance through one or two small windows, but their only source of interaction was daily Mass that they observed through a window looking into the church. Before they entered the room, they were declared “dead to the world.”

For their thesis, “‘Mi bodi henge wið þi bodi’: Dying with Christ in the Anchorhold,” Grissom’s analyzed two medival anchorite texts, Ancrene Wisse, and Þe Wohunge of ure Lauerd that served as sort of instructional texts.

Senses and Sin

“I was wondering, ‘What in that restrictive process makes it so useful for their spiritual work, and how are their instructional texts helping them imagine their bodies differently in order to do that work?” said Grissom, who will graduate with a Master of Arts from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) in May.

“In my research, I ended up thinking a lot about the senses because some medieval theologians and philosophers thought that women’s bodies were more connected with the senses, and through the senses, with sin.”

Courtesy of Alice Grissom

What stood out most in their analysis of the documents was that for an Anchorite, declaring themselves dead and embracing sensory deprivation was not the end of the story. By cutting off their traditional senses, the Anchorite was in fact awakening their “spiritual senses,” and growing closer to God.

“I was really surprised to see that there is this recuperation of the senses in spiritual work. Rather than just this straightforward narrative that medieval men are always suspicious of medieval women’s bodies and their senses, it’s a lot more complicated and nuanced,” they said.

Grissom was drawn to medieval studies because it offers the same sort of interdisciplinary scholarship that they enjoyed as an undergraduate majoring in English and history at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. There, they found themselves studying humanities at a science-heavy institution; and the experience gave them a greater appreciation for the interplay and blend of different disciplines.

Linguistics and Medieval Literature

Another draw for Grissom was the opportunity to delve deep into linguistics.

“A really big turning point for me was taking a history of the English language course. It was one of the coolest things I had ever done, getting to see how language changed over time,” they said. “It provided so many insights into the ways that we as people and societies change as well.”

In March, Grissom tied for second place in the GSAS three-minute thesis competition, an annual gathering where graduate students boil down their research projects for the general public.

Last year, they were the recipient of a GSAS Student Support Grant, a Mary Magdalen Impact Fellowship, which supported a research trip they took to Prague last summer, and a Fordham Jewish Studies Fellowship. In 2021, Grissom was also awarded a Loyola Fellowship, an award established by the Jesuits of Fordham that allowed them to develop digital humanities projects, run and attend language reading groups, co-organize a symposium, and develop and submit abstracts for conferences.

New Medievalists: Establishing the Diversity of the Past

In the fall, Grissom will be pursuing a Ph.D. in English at Rutgers University and plans to combat the misappropriation of medieval history by groups such as white supremacists who use Nordic runes to symbolize white supremacy.

“By showing that these are inaccurate uses of the past and that the past was a lot more diverse, a lot of us newer medievalists are trying to establish a historic precedent for the diversity of the present,” they said.

Andrew Albin, Ph.D., an associate professor of English who directed Grissom’s Fordham thesis, said their work illustrates a creative use of the few surviving materials to tell the story of the lived lives of people in the past.

“It humanizes people from the past who might feel really alien to us. The idea of choosing to wall yourself up inside a six-by-six cell for the rest of your life just so that you can pray feels kind of outlandish,” he said.

“It is a kind of practice that we don’t really have an imaginative space for anymore inside our culture. Rather than exoticize it and play up the kind of strangeness of it, [Grissom] tries to get inside the experience.”

Album said Grissom has also shown a knack for building community, reaching out to graduate students in the English Program and moderating panels at a conference for a New York area consortium of Medievalist scholars this month. He called them a natural-born teacher.

Equally important, he said, is Grissom’s commitment to addressing issues of race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, and disability.

“They have a really remarkable way of finding connections between those political commitments and the work that they do, and of making sure that there’s always a conversation between the kinds of questions that we care about today and how that impacts the kind of work that they take on,” he said.