Three-dimensional (3D) printing has led to breakthroughs in various industries across the board, from automotive and consumer electronics to education and aerospace. But engineering physics student Marissa Vaccarelli, a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior, believes the technology is especially primed to solve critical problems in the field of prosthetics and biomedical engineering.

“3D printing is growing,” said Vaccarelli, who will be participating in Fordham’s inaugural Women’s Philanthropy Summit on Nov. 6. “People are not only able to design pieces, but also design parts that are functional and useful for humans.”

In the United States, there are nearly two million people living with limb loss, according to the Amputee Coalition. The organization also reports that among the individuals living with limb loss, 54 percent were a result of vascular diseases such as diabetes and peripheral arterial disease. Approximately 30 million people in low-income countries require prosthetic limbs, braces, or other assistive devices, according to the World Health Organization.

“Prosthetics are very expensive,” said Vaccarelli. “Limbs that function as human limbs [can]cost up to hundreds of thousands of dollars, so 3D printing is a nice alternative. It’s very cost-effective, and the time to manufacture is pretty short.”

This past summer, Vaccarelli, a 2017-2018 recipient of a Clare Boothe Luce Award, worked in the Engineering and Design lab under the supervision of Stephen Holler, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics, and the department chair and professor of physics Vassilios Fessatidis, Ph.D., to conduct research on prosthetics.

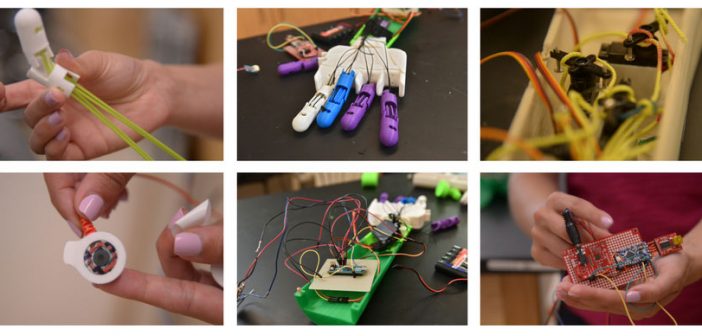

She aimed to modify e-NABLE Raptor and Limbitless Flexy-Hands—the lab’s existing artificial limb models. She built a 3D prosthetic hand, wrist, and forearm using SolidWorks, an industry standard solid modeling software, and Makerbot, a high-quality, low-cost desktop 3D printer. The goal was to create a more flexible and functional prosthetic hand equipped with muscle sensors, pulse monitors, and temperature readers, she said.

“The very first thing we did last year was build a finger,” she said. “It’s a three-part finger so it has two hinges, and it basically opens and closes like a human finger. We have two sets of strings, and we kind of pull them like a puppet, and those are attached to motors. All of the circuitry is housed in the forearm that we designed as well, and it also extends to the elbows.”

However, while the mini-motors in the forearm were able to rotate and create motor movements, the finger movements were unstable.

“Those had uncoordinated finger motion, so basically they would just [move] as if they were playing a piano,” she said. “But this [past] summer, we wanted something better. We wanted an object that would grasp things.”

Vaccarelli tested the finger movements on a breadboard and later used Arduino, a microcontroller on a circuit board that reads and controls the inputs and outputs. Since muscle sensors are able to pick up differences in voltage when people flex and contract their arms, Vaccarelli plans to implement new muscle sensors in a model that uses electromyography. This could lead to enhanced motor control in the lab’s latest prosthetic prototypes, she said.

“This project is important because while it’s scientific research, it’s also doing common good for the public,” she said. “It’s really bringing a lot of awareness to how important 3D-printed prosthetics are. It’s a huge community, and there’s limitless possibilities to using science and technology to help humans as well.”