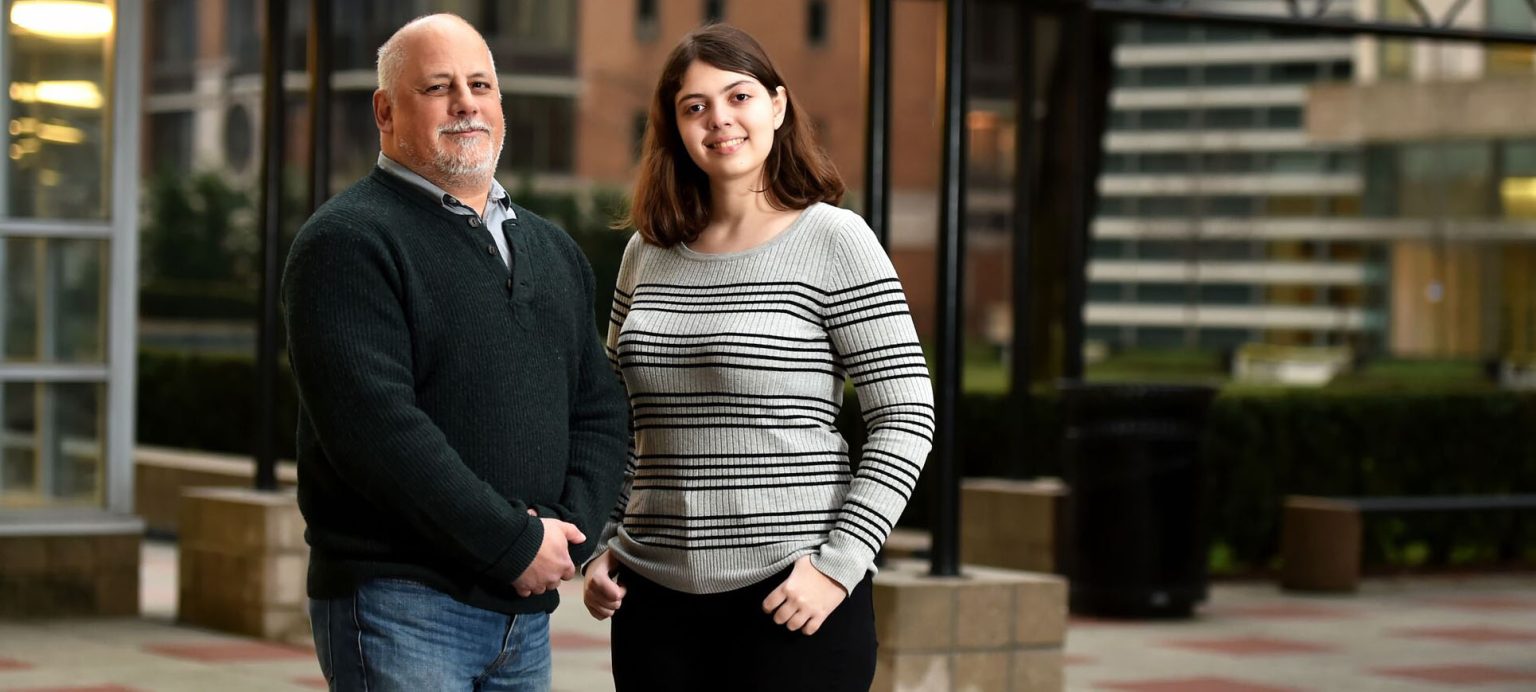

When Mitchell Rabinowitz, Ph.D., a professor at Fordham, agreed to serve as a supervising scientist on a research study with Isabella Greco, a student at the Bronx High School of Science, he wasn’t sure what to expect.

“I started off suggesting things to her, and she said, ‘No, I want to work on gender stereotyping and careers,’” said Rabinowitz, a Graduate School of Education faculty member who had never mentored a high school student before. “She read my articles and research, and we came up with a methodology and related it to the topic.”

With Rabinowitz’s help, Greco researched the impact that gender association, and consistency or inconsistency with gender stereotypes, had on a person’s ability to accurately remember biographies about one’s occupation.

This January, Greco’s study, “The Effect of Gender Stereotype and Stereotype Inconsistency on False Memory of Occupation Descriptions,” was named a finalist in the Regeneron Science Talent Search, the nation’s oldest and most prestigious pre-college science competition. Only 300 students are announced as semifinalists each year. From that pool, 40 students are named finalists. According to Regeneron, alumni of the science talent search hold more than 100 of the world’s most distinguished science and math honors, including the Nobel Prize and National Medal of Science.

In March, Greco will join other Regeneron finalists in Washington, D.C. to present her research to the public, meet with renowned scientists at the National Geographic Society, and undergo final judging. She will also compete for the top 10 awards, which range from $40,000 to $250,000 for the first place winner. The top 10 winners will be announced at the National Building Museum on March 14.

“It’s an honor to be a finalist in Regeneron,” said Greco, one of seven Bronx Science students selected and the only finalist among them. “Especially since there’s this idea that math and natural sciences are harder and more important.”

In the study, Greco recruited participants for an online survey that asked men and women to assess statements about six biographies they were shown. The survey revealed that false memory formation was a factor in lower valuation of feminine-associated occupations that were mentioned in the biographies. Participants remembered job descriptions with feminine stereotypes, such as nursing and teaching, with significantly less accuracy than job biographies associated with masculine stereotypes, in particular engineers or pilots.

“For the feminine jobs, people not only had more false memories, they also remembered those jobs as being less important—or more specifically the person not achieving as much in their jobs.”

“This was the same whether the person in the job was a man or woman,” Greco said.

Rabinowitz said Greco’s study had many implications.

“You can relate it back to the implicit cultural bias that people have that they’re not aware of,” he said. “These implicit biases just came out and affected how they interpreted information.”

As the gender-pay gap continues to be a hot topic in the workplace, Greco, who plans to study psychology in college, said she hopes her research paper would not only shed light on gender bias but inspire action, too.

“It’s important to examine how these biases are created [in order to determine]how we can get people to rely less on them,” she said.

Greco, who is only formally taking AP psychology this year, credits Rabinowitz with providing the resources, expertise, and counsel required to produce a compelling study.

“I had to do a lot of research independently of any class,” she said. “Professor Rabinowitz was very open and supportive. He’d say, “What are you interested in doing and how can I help?”

In the end, the partnership proved to be mutually beneficial.

“This is a great example of outreach from the university to the community,” said Rabinowitz. “I got to work with a very good student, and we came up with a study with interesting results.”