The “War of the Currents,” as the competition between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse in the 1880s was dubbed, was vicious, unrelenting, and in the end, futile for Edison, as his campaign to discredit Westinghouse’s alternating current (AC) in favor of his own direct current (DC) failed.

But Benjamin Cole, Ph.D., says the feud between the dueling inventors, which became intertwined with the evolution of criminal executions in the United States, can teach us a lot about the value of competition in business.

Cole, the William J. Loschert Endowed Chair in Entrepreneurship and an associate professor of strategy and statistics at the Gabelli School of Business, recently published a paper on the topic after five years of extensive archival research. “A Model of Competitive Impression Management: Edison versus Westinghouse in the War of the Currents,” ran in the prestigious journal Administrative Science Quarterly in January. The journal, which publishes only a small fraction of papers submitted to it, is routinely used in doctoral-level business classes.

He said that the paper, which he co-authored with David Chandler, assistant professor of management at the University of Colorado Denver Business School, shows how even a brilliant scientist like Edison could allow himself to be overcome with the desire to destroy his competitor’s reputation.

“When I began this paper, I never thought that my conclusion would be, ‘Wow, George Westinghouse is a really incredible human being, we should make a movie about him, and, ‘Boy, Edison was a real jerk,’” he said laughing.

A Gruesome and Disturbing History

Although we take for granted the safety measures in place today that allow us to seamlessly harness the power of electricity, in the late 19th century, the public’s trust of the technology was still in flux.

Cole, whose research also includes Blockchain technology, said he became interested in the topic when a colleague at the 2014 Academy of Management’s annual conference told him he’d discovered a collection of data that detailed every single execution in the United States, along with the technology that was used.

The electric chair, he came to learn, was invented as a more reliable, and thus, it was thought, more humane alternative to hanging. New York state was a pioneer in the area, with Governor David B. Hill establishing a three-member commission in 1886 to explore the issue. Edison was one of the people whose opinion was solicited, and his response was to suggest the state use Westinghouse’s alternating current to do the deed.

“Edison saw this as an opportunity. He said, ‘If I legitimize alternating current for executions and equate it with death and danger, then I can actually delegitimize it for use it there, because people will be scared to have it in their homes,” Cole explained.

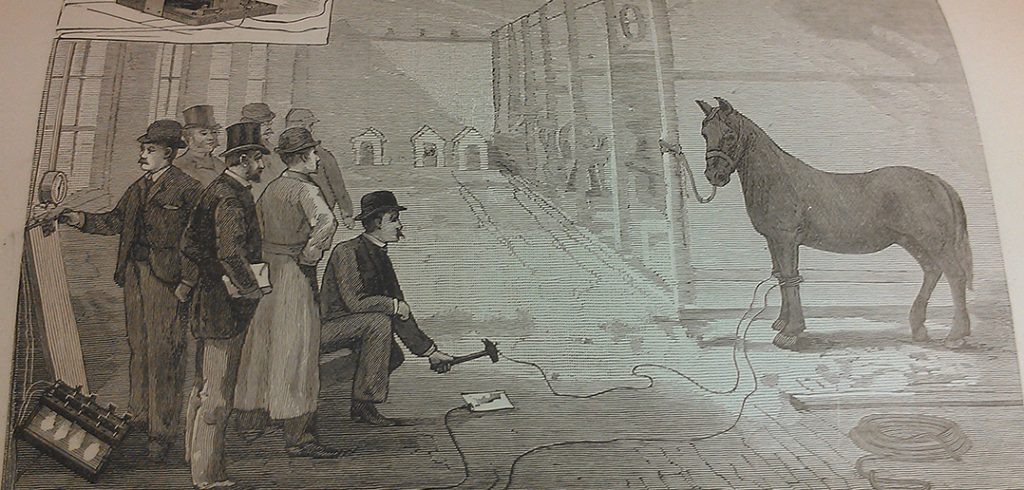

Edison did succeed at showing how AC power could be used to kill, through a series of gruesome public demonstrations in Manhattan, in which dogs, calves, and horses were electrocuted. On August 6, 1890, the State of New York used an AC-powered electric chair to execute a convicted murderer named William Kemmler, making him the first person in the country to be executed this way.

Edison went so far as to pay to distribute the findings of the animal executions to every single business person or politician in the United States from a town of a population 5,000 or larger, but he ultimately failed to connect AC power with death in the public’s mind. Today, AC is used to transport electricity around the globe.

Worse yet, Cole said his negative campaign inadvertently pushed Westinghouse to innovate as well.

“Westinghouse recognized Edison’s tactics for what they were, so he decided to kind of pivot,” Cole said.

In addition to taking steps to assure the public that AC power could be delivered safely, Cole said Westinghouse also showed how it could be scaled up, most dramatically when he was picked—over Edison—to demonstrate that he could illuminate the entire World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. He thus proved that long distance was not an obstacle to AC power.

“Westinghouse said, ‘I think people are willing to accept some risk if we can deliver on the cost front. Because if we can make it so that power is available to everyone, and you could put a generator on Niagara Falls and feed power to almost the entire state of New York, that type of system would be very, very, powerful.”

What ultimately doomed Edison’s quest to discredit AC power and promote DC, is that while DC power is less likely to inadvertently electrocute a person, it can only travel for a mile, whereas AC power travels much further on its own. DC power is still widely used today; it’s what flows through our electronic devices. But AC is what power plants generate and send to our houses and businesses.

Lessons for Today’s Business

Why would this be relevant today? Cole noted that Uber and Lyft recently illustrated how companies still actively work to undermine each other, by secretly ordering and canceling thousands of rides to increase each other’s operating costs and frustrate their customers. Firms regularly steal from and spy on each other, fund fake research to mislead political actors and customers, and bribe the media for desirable portrayals, he said, demonstrating the belief that success comes not just from being the best in the market, but also being perceived as better relative to competitors. Although this belief has some merit, Cole said there is a danger in relying on it. Edison’s example shows how a business that spends an inordinate amount of time besmirching its competition will neglect to innovate, he said, and suffer in the long term as a result.

Ultimately, though, competition matters.

“Competition actually drives innovation and we benefit as a result of that,” he said.