Evangelical Christians have long acknowledged that anti-intellectualism has plagued their religious tradition. As Evangelical historian Mark Noll put it in 1994, “The scandal of the evangelical mind is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.”

Scholars have linked this anti-intellectual bent to a variety of influences—for instance, the growing insularity of the Evangelical community, or the sway of charismatic church and political leaders. However, James Van Wyck, an English doctoral student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, believes that it in fact stems from something seemingly innocuous: the last century-and-a-half of fictions that Evangelicals have been reading and writing.

To prove his point, Van Wyck has taken a daunting plunge into the archives to chronicle Evangelical literary trends and how these have influenced contemporary Evangelical thought. He argues in his doctoral dissertation that 19th-century Evangelical texts relied heavily on an appeal to readers’ emotions, a technique born from a sentimentalist ethos that continues to inform Evangelical reading habits today.

(Photo by Karen Mancinelli)

Emotional value

According to Van Wyck, 19th century religious fiction was used to evangelize to “unsaved” readers and push a particular Christian social and moral agenda. To do so, Evangelical writers tended to emphasize “emotional utility over intellectual stimulation,” Van Wyck said. Books such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin were written to make people “feel right,” as Harriet Beecher Stowe herself put it.

“Evangelicals retain an old, mid-19th-century understanding of fiction as a utilitarian instrument,” said Van Wyck. “A work of fiction does something to you. They want fiction to make you think right, feel right, and act right—to guide you on your pilgrimage to heaven.”

Contemporary Evangelical authors such as Janette Oak, Beverly Lewis, and Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins—co-authors of the popular end-of-times book and movie series, Left Behind—carry on this sentimentalist tradition. What separates them from their predecessors, though, is that contemporary Evangelical fiction is produced and consumed by an insular audience. Consequently, these authors aim to provide an emotionally gratifying experience for Evangelical readers, rather than to explicitly convert non-Evangelicals.

Topping the bestsellers lists

However, there is more to this story than simply illuminating the sentimentalist roots of Evangelical anti-intellectualism, Van Wyck said. Novels written by Evangelicals dominated the literary marketplace in the mid-19th century. The sheer numbers warrant a closer look, as Evangelical fictions have distinguished themselves as some of the most strikingly popular works in the American literary canon. In 19th-century terms, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was as popular as Harry Potter. Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World was acclaimed by author Henry James and artist Vincent van Gogh.

And today, though they tend to no longer attract non-Evangelical readers, these fictions boast sales in the hundreds of millions of copies and consistently top the bestsellers lists—seven of the Left Behind series reached #1 on New York Times bestsellers lists.

(Photo by Karen Mancinelli)

“Most of us in the literary criticism business got into it by reading the classics, which don’t generally encompass these religious bestsellers,” said Van Wyck’s dissertation adviser, English Professor Leonard Cassuto. “But there was a moment when I realized that the American literary tradition as it was presented to me is bigger than I thought it was.

“For me, and other critics too, there is an evolving realization that we can’t understand the book markets of the 19th century unless we also widen our view to encompass the role of religious fiction,” Cassuto said. “James Van Wyck has taken a remarkable route into the archives to do this. Nobody has ever looked so closely at how Evangelicals actually read, and at what they were taking into account when they did so.”

But do they have an impact on anyone outside of religious circles? Van Wyck thinks so.

“Ronald Reagan, who charted much of the course of international and American identity in the 20th century, ascribed his conversion to Christianity to the book That Printer of Udell’s, which he read as a young boy,” Van Wyck said. “His whole worldview was essentially informed by a book that is all about the individual’s relationship to God and how that changes after a conversion experience.

“[To that end, one could say] Evangelical fiction has altered the course of history.”

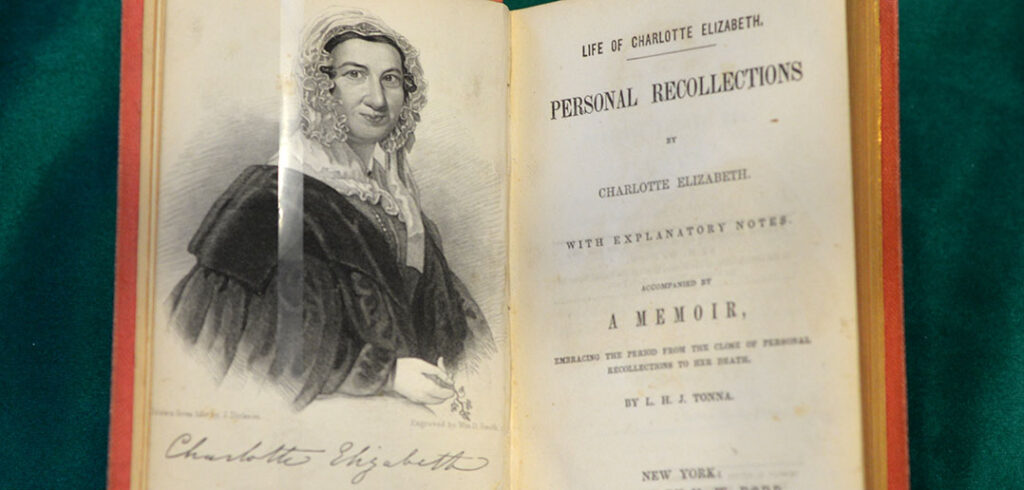

- In November, Van Wyck teamed up with Christopher Anderson, Ph.D., the head of Special Collections, Archives, and Methodist Librarian at Drew University, to showcase his research in a special exhibit running at Drew from November through February. The exhibit takes a closer look at some of the Evangelicals—particularly women and writers of color—who penned successful fictions of their day.

“When it comes to women writers or writers of color within religious circles in the 19th century, we’ve gone an inch wide and a mile deep,” Van Wyck said. “We know a great deal about writers such as Stowe and Warner, yet we’ve failed to situate them in their original context. Our exhibit is an attempt to begin to remedy this.”

In addition, the exhibit examines Evangelical writers’ use of diverse modes of publication, such as serialized fictions found in magazines and newspapers. Not only were these outlets cheaper and more widely distributed, but they also offered more opportunities for women, African Americans, and other minority populations to publish.

“Periodicals bound far-flung communities together,” Van Wyck said. “When you look at them more closely, you find that they contained more diversity than you’d think.”

At the opening of the exhibit on Nov. 11, Van Wyck presented, “The Legacy of Evangelical Fiction,” and Cassuto spoke on “Religion and the American Bestseller.”

Click the photos below to view a gallery. (All photos by Karen Mancinelli)