Like most Black indigenous people of color communities throughout the nation, many of the event’s participants have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. In addition, the community is coping with a rash of violence against native women that has not received widespread national attention. Kevin Tarrant, founder of Silvercloud Singers, the inter-tribal group who had performed as host drummers at the past three festivals, died of COVID-19 in May. And Sheldon Raymore, who performed last year and was set to perform this year, pulled out because he was mourning the death of his cousin who was killed in October.

“Native people have a lot of experience of pandemics: 90% had died within 200 years after Columbus arrived with European smallpox. It’s amazing so many of us are alive today; now [a pandemic]is affecting us again,” said Bobby Gonzalez, the Bronx community organizer who liaises each year with OMA to help organize the festival.

Gonzalez, who is Taíno by way of Puerto Rico, provided historical context for the event in a talk titled “American History Through Native Eyes,” which he described as “500 years in 15 minutes.” In his speech, Gonzalez drew a connection between “man camps,” makeshift housing for nonnative pipeline workers, and women disappearing from reservations.

“These camps are all men, we call them “man camps,” he said. “Thousands of native women have been kidnapped, sexually abused, and murdered and very few people have been convicted because it was difficult on a reservation for natives to arrest nonnatives. Federal laws have stipulated that the federal government has jurisdiction, and it wasn’t a priority until only this past September when Congress passed the Savanna’s Act and the Not Invisible Act.”

Gonzalez’s talk outlined many atrocities perpetrated against native peoples, but he ended his talk stressing their resilience, noting the more than 2.7 million living in the U.S.; over 1.5 million in Canada; and 50 million in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

“We survived pandemics, we survived catastrophes, and we’re still here,” he said.

He attributed recent strides to finding common purpose with the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the LGBTQI community and “other suppressed peoples.”

The notion of strength and solidarity in community was underscored in dance, song, and stories performed by Ty Defoe, the Grammy-winning performance artist and activist who broadcast from his apartment in Brooklyn. Defoe grew up in the Ojibwe and Oneida traditions and identifies as two-spirit, a term used to describe gender fluidity.

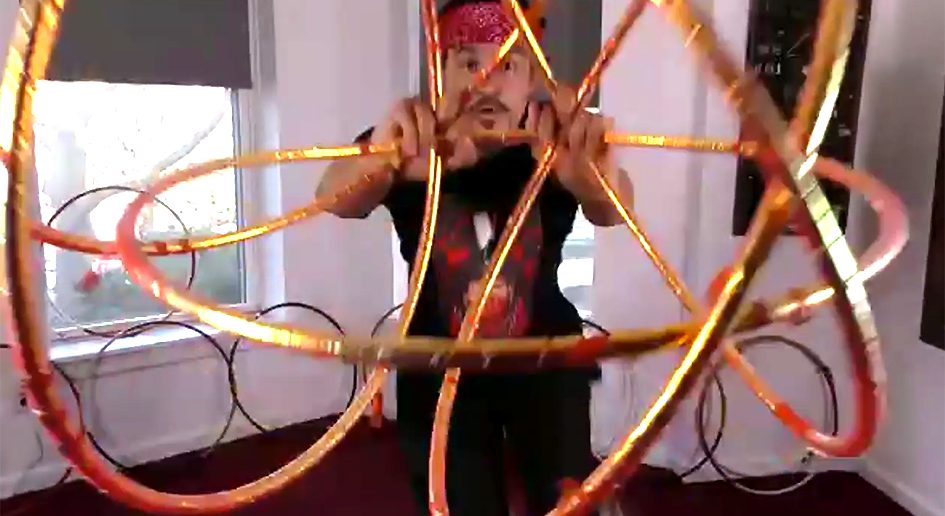

Defoe performed a hoop dance in conjunction with a story about a native youth whose brothers and sisters were fighting. The youth was gifted a hoop by a god, who told the youth to make as many things in nature as they could and their people would become stronger each year, providing peace and resistance. The young person gathered red willow that grew by the river to make the hoops.

“You can still see this red willow over by the Hudson and the East River, it’s very flexible so you can make these circular shaped objects,” he said.

The youth danced with the hoop, the story goes, and made trees, flowers, animals, and butterflies.

“They did that dance and went back to their village and there were their brothers and sisters fighting with their fists in the air and when the dancer came with all of those hoops around them, the brothers and sisters stopped and dropped their fists in midair and said, ‘Holee wah!’ Holy Cow! Let me try that dance.”

That is how they formed what is now known as the people’s hoop dance.

“It is said that no matter who you are, no matter what race, tribe, religion sexual orientation, gender, age—no matter who you are you are part of this hoop, a part of this sacred circle.”