Writers and poets rarely get to display their words beyond the pages of a book. Many don’t wander beyond traditional structures—haikus, sonnets, odes, villanelles, and more.

But poet Elisabeth Frost’s new collaboration with visual artist Dianne Kornberg creates interplay among words and images, giving new form to both mediums and inspiring new possibilities in which to imagine expression.

Bindle (Ricochet Editions, 2015) took root when a curator chose Frost and Kornberg to create a visual installation for the 2009 Poetic Dialogue Project.

“We did not know each other,” said Frost, a professor in the Department of English. “Luckily, we liked each other’s work right away.”

Tasked with creating a collaborative exhibit of their work, the two artists spent a week at Kornberg’s studio in the San Juan Islands north of Seattle. There, Frost became inspired by Kornberg’s interest in specimens collected for scientific study and her photographs of the natural world.

The result was a series of diptychs called “Arachne,” a blend of Kornberg’s photo-based images with Frost’s writing, inspired by a metaphoric interest in spiders and their webs.

Frost and Kornberg have continued to collaborate ever since. Bindle reproduces a selection of their work in book form for the first time.

“Arachne,” which makes up one section of the book, represents the stages of a spider’s life—launching its web, building an intricate structure, waiting passively for prey, and consuming food.. The last image ruminates on the Greek myth of its namesake, the woman-turned-spider.

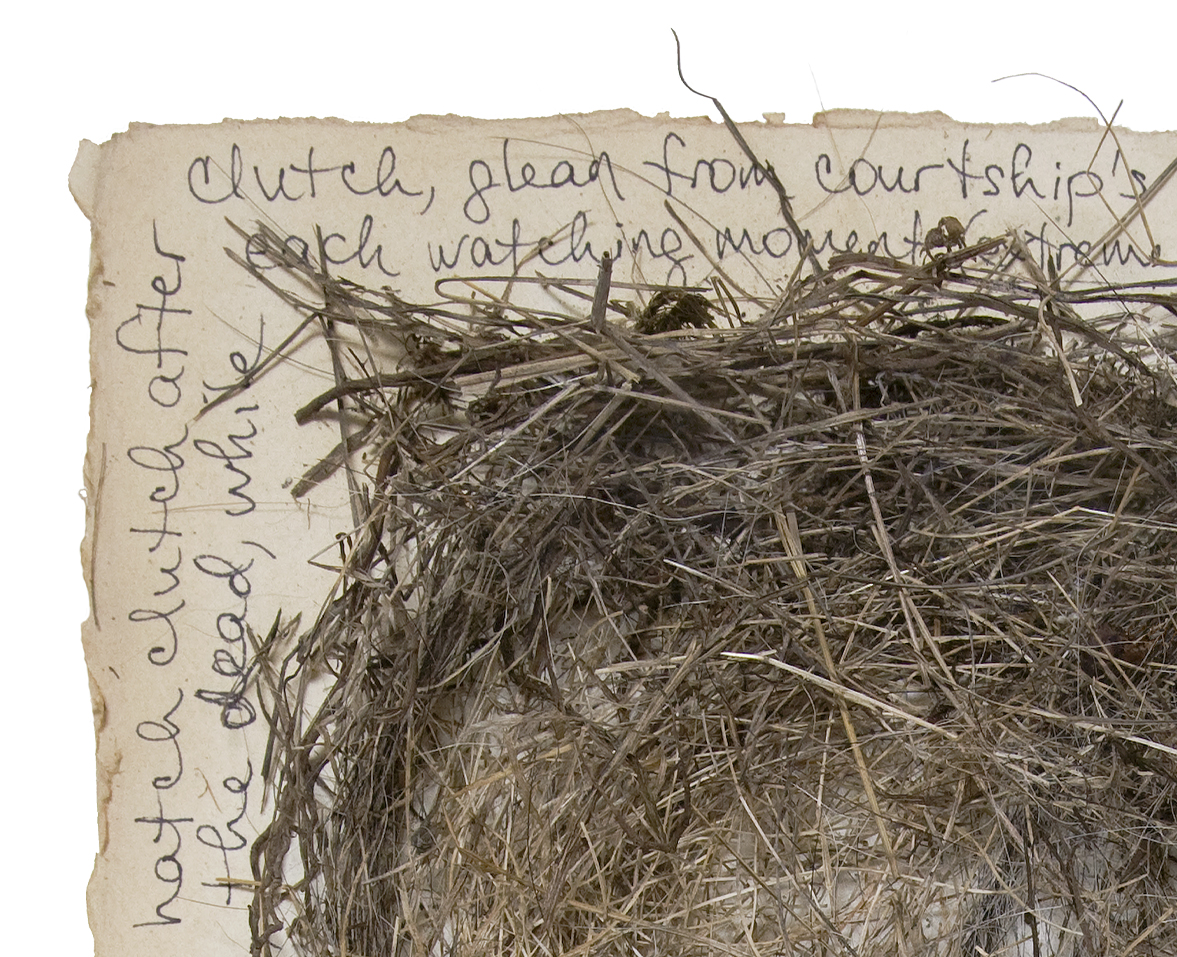

Bindle’s theme of home and transformation in the natural world is explored in two more sections. The first features a series of photos of birds’ nests, in which Kornberg and Frost contrast scientific and poetic ways of interpreting them.

Bindle’s theme of home and transformation in the natural world is explored in two more sections. The first features a series of photos of birds’ nests, in which Kornberg and Frost contrast scientific and poetic ways of interpreting them.

The images incorporate Frost’s research-based text derived from both Romantic poems and 19th-century manuals describing the popular ladies’ hobby of nest collecting (caliology).

“Collecting nests was a class-based activity for the wealthy; at the same time, the fact that such a hobby was making a dent into the male-dominated field of scientific inquiry was fascinating to me,” she said.

In the third section, Frost and Kornberg took inspiration from their monthlong artist’s residency in Oysterville, Washington, where they saw the mounds of oyster shells following the harvest. On the page, Kornberg’s complex, textured photos of shell-piles sit atop of Frost’s poetic phrases describing something that “is left.” In this case Frost’s words are extracted from a grief-based poem written for her late mother.

“These mounds of shell become emblematic of mortal remains and a parallel theme: ‘where does a creature live, and what does it live in?’ A web? A nest? A shell?,” she said.

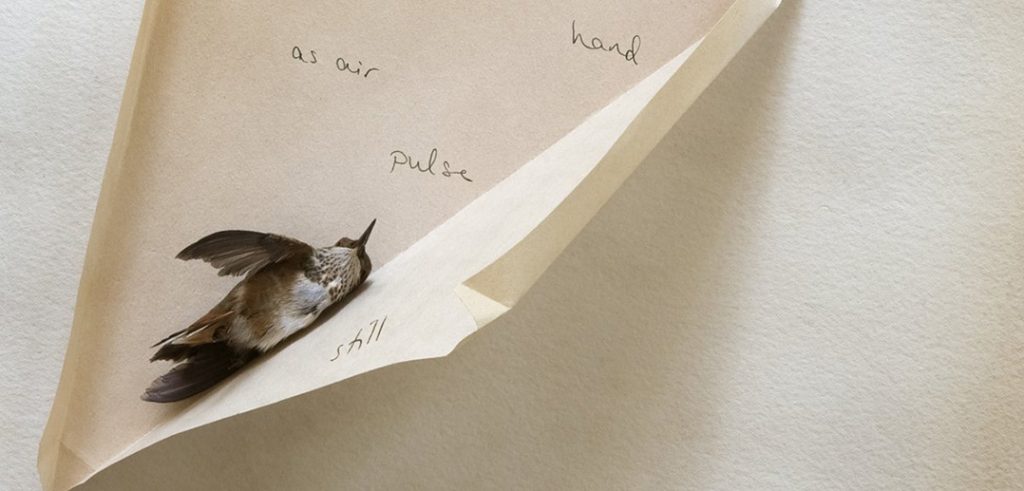

The title work, which concludes the book, is a single image of a dead bird held within a folded sheet of paper. Frost’s handwritten words, a poem about death and loss, travel across the white space: “light as air in hand pulse still.”

Read excerpts of commentary on Bindle by Alicia Ostriker and Terri M. Hopkins. (all images courtesy Ricochet Editions.)

— Janet Sassi