According to Fordham’s Center for Ethics Education, more than one million violent offenders are serving time in state prisons in the United States, a number that is rapidly outstripping the nation’s capacities and challenging Americans’ conceptions of how incarceration should function.

On Oct. 12 at the Lincoln Center campus, the center co-hosted a distinguished panel of experts on the topic of “Mass Incarceration and Violence: Are We Overpunishing Violent Offenders?”

The panel’s focus on the sentencing of violent offenders was partly in response to the common misconception that prison overcrowding is due to over-prosecution of low-level crimes like drug (marijuana) possession. Contrary to popular belief, however, “nonviolent offenders,” said theologian Anthony B. Bradley, GSAS ’13, “are not the reason we have a crisis in our prisons,” and reducing non-violent incarcerations alone will not fix the problem.

Fewer Crimes, Longer Sentences

Fordham Law alumnus Barry Latzer, Ph.D., emeritus professor of criminal justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, analyzed different sets of statistics to illustrate patterns in incarceration both historically and internationally. He cited data showing that the current median time served by violent criminals in the United States has reached historic highs, even though crime levels have dropped from their 1970–1993 peak—a period Latzer characterized as a “tsunami of crime.”

In addition, time served for various violent crimes in the United States, according to Latzer, exceeds an average of time served in comparable nations by anywhere from 11.6 months (assault) to 31 months (homicide).

Rutgers University Professor of Philosophy Douglas Husak, Ph.D., brought a philosophical facet to the conversation, pointing out that incarceration traditionally has an “expressive dimension” that serves the role of a “public condemnation of stigma.” He suggested that “when in doubt, don’t punish” might be a useful moral guideline in reshaping America’s attitudes toward incarceration.

Columbia law professor Brett Dignam said there are structural challenges in the process of parole review; that and other problems make it “an opaque system” dominated by overworked parole commissioners faced with undereducated potential parolees.

“They literally don’t have enough time to do their jobs,” she said.

A Complex Problem

All three panelists agreed that the challenge of reducing incarcerated populations was complex and demanding, requiring both committed resources and intelligent planning. Their conversation repeatedly turned on the theme that criminal justice has mixed objectives, combining elements of deterrence, public safety, and moral retribution—concepts that do not always align in practice.

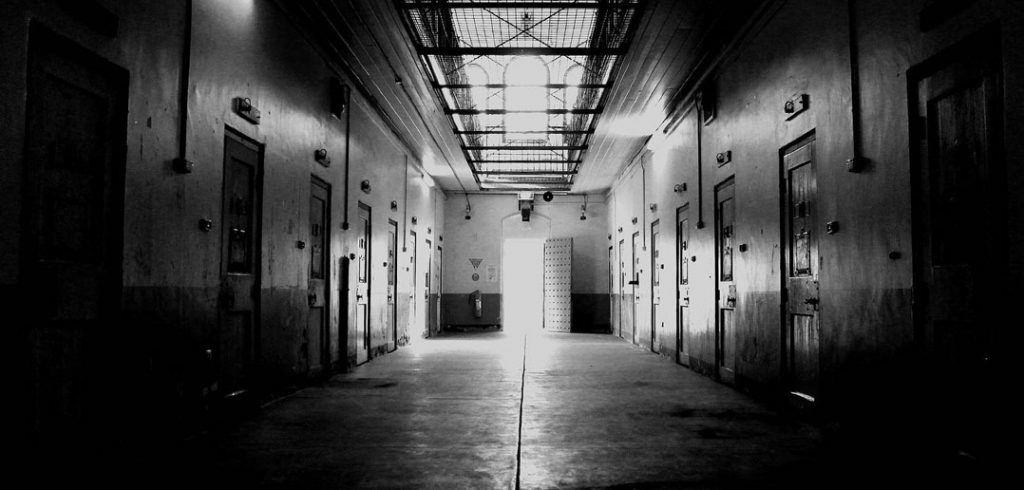

The panel, which was co-sponsored by the Center for the Study of Human Flourishing at The King’s College, concluded with a lively Q & A session moderated by Bryan Pilkington, director of academic programming at Fordham’s Center for Ethics Education. (Photo by mammovies, creative commons)

— Michael Lindgren