On May 7, Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum will debut an exhibit of rarely seen art examining the wakashu, pubescent youths considered desirable by both men and women in 18th-century Japanese society.

The exhibit represents the culmination of a productive post-doctorate project by Fordham’s Asato Ikeda, PhD, assistant professor of art history, also the exhibit’s curator.

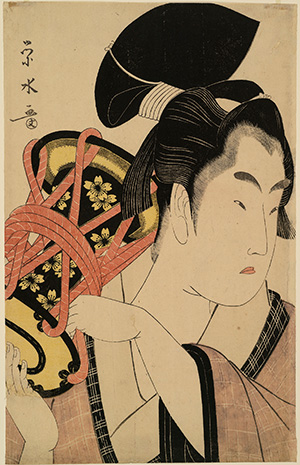

(Courtesy ROM collection)

Ikeda culled “A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints” from more than 2,500 Japanese woodblock prints in the museum’s collection, the largest of its kind in Canada. The images depict adolescent males in Edo-period Japan, who have yet to go through the traditional coming of age ceremony but who were considered sexually active and attractive by the society.

“In the exhibition we’re developing a new definition of gender,” said Ikeda. “It’s not just determined by biological sex, but also age, role in sexual hierarchy, and appearance.”

By focusing on the topic of gender and sexuality, the exhibit provides relevance to contemporary audiences grappling with the issue, said Ikeda.

Most of the prints are from the Edward Walker Collection, which was given to the museum in 1926, but were largely underexplored. With Ikeda’s expertise in Japanese art, the museum was able to begin an overall assessment, while simultaneously curating a show.

“There were boxes that nobody had opened for years,” she said. “It was very challenging because not much was on the museum database, so we had to record all of the information.”

(Courtesy ROM collection)

The museum kept a blog of the process, but outside of the database and blog very little of the collection has been seen online. Digitizing would be a costly 5-to-10-year process, said Ikeda. As such, the exhibition represents a rare opportunity not only to examine the wakashu, but also an opportunity to view significant pieces from the collection.

“The museum collection is so comprehensive that we were able to choose such a specific theme,” she said.

Ikeda collaborated on the project with Joshua S. Mostow, PhD, an expert in the gender structure of Japan’s Edo Period, which lasted from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

In the process, the curators consulted with the Canada’s LGBT community, social workers, and activists through workshops. The concept was very well received with great interest in the historical aspect of gender issues and appreciation that an established museum would explore the subject in in such depth, said Ikeda.

“We try to be clear that the wakashu are not identical to LGBT culture today,” said Ikeda. “But certainly its culture is very important in terms of thinking about diverse gender and sexuality practices.”

“For example, the word ‘gay’ is very specific to our contemporary culture. It’s very democratic, egalitarian, and individualistic, and you have claim to your identity. In 17th-century Japan, however, you couldn’t really claim your identity. It was imposed on you by age, gender, and class.”

A section of the exhibition is dedicated to contemporary identity issues, but some of it is also devoted to different gender and sexual norms and ideals—from the pederasty of ancient Greece to 19th-century binary gender norms in Victorian England to the “two spirited people” of the first nations.

Traditional Form, Edo to the 20th Century

Ikeda’s own area of research and expertise centers on fascist paintings celebrated by the Japanese government and authorities during World War II. “The desire was to return to quote-unquote ‘traditional,’” said Ikeda, “The fascist paintings don’t look violent and don’t show soldiers, but those peaceful looking paintings were meant to evoke pride in Japanese traditions and justify the war against the West.”

When Ikeda was young, stories her grandfather told her sparked an interest in the fascist art. He was from southern Japan, where the kamikaze planes lifted off.

“My grandfather was obsessed with kamikaze and he was ultranationalist,” said Ikeda.

She noted that only since the turn of the century did scholars begin to look at Japanese wartime art. The dominance of the Japanese right-wing in politics, which resulted from the strong U.S.-Japan alliance since the Cold War, prohibits the kind of self-examination engaged in by German people after World War II, she said.

“Japan has trouble understanding this part of history,” she said. “In Germany you can’t deny the holocaust and the Germans collectively tried to be apologetic, but that’s not the case for Japan, where people can publicly claim that the Nanking massacre never happened. There is no consensus. Basic historical facts continue to be contested and dismissed.”

As she worked on her soon-to-be-published book, Soldiers and Cherry Blossoms: Japanese Art, Fascism, and World War II, she discovered that some relatives of wartime artists remained resistant to allowing her to publish the material.

In both the case of the wakashu and the case of the fascist art, Ikeda is taking an unflinching look at history; however, she refuses to make a judgment call on whether the art is good or bad. That, she said, is not an art historian’s job. Instead, her job is to situate artworks in historical context.

“The art is not just important historically, it’s very important politically and ethically,” she said.