Although there are specific locations that cultures place great importance on, from landmarks to shrines, each of us also has our own, personal spaces that are sacred to us.

For Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, a new book of poetry serves as a tribute to both types of “holy lands,” be they far or near.

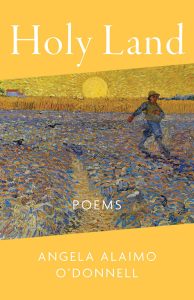

Holy Land, (Paraclete Press, 2022) a collection of 87 poems that won the Paraclete Press Award in 2021 and was published in October of this year, was in fact inspired by a trip that she took to Palestine in 2019.

The first chapter, Christ Sightings, is based on her time in Palestine. What follows is a series of chapters—Crossing Ireland, Ancestral Lands, Sounding the Days, Literary Islands, and Border Songs—that were inspired by her travels to places that may not be the Holy Land, but are holy to her just the same.

Crossing Ireland features poems O’Donnell composed after visiting the Emerald Isle, while Ancestral Lands features meditations on her native northeast Pennsylvania. The poems in Sounding the Days and Literary Islands expand the notion of holy lands into the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual realms. The book ends with 15 triolets inspired by the crisis at the United States-Mexico border that dominated the news in 2019.

Crossing Ireland features poems O’Donnell composed after visiting the Emerald Isle, while Ancestral Lands features meditations on her native northeast Pennsylvania. The poems in Sounding the Days and Literary Islands expand the notion of holy lands into the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual realms. The book ends with 15 triolets inspired by the crisis at the United States-Mexico border that dominated the news in 2019.

The book’s first poem, “The Storm Chaser,” was inspired by a visit to the Sea of Galilee. The view of the sea has changed little in the 2,000 years since Jesus and his disciples were said to have spent time there, so O’Donnell said it was easy to create a picture in her head of what it would have been like then.

Running along the Sea of Galilee,

I see you in your boat, tall brown

man that you are, standing in the prow,

“All of these stories that I had been hearing all of my life in church in the Gospel readings suddenly became so much more powerful and real when I was in the landscape where they unfolded,” she said.

“There was something electrifying about walking literally in the footsteps of Jesus and being in those spaces where these events took place.”

As moved as she was by the geography there, O’Donnell said she knew didn’t want to limit herself strictly to one location.

“It’s arguable that there are no places that aren’t holy, that aren’t sanctified in some way by human experience,” she said, noting that Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, is considered sacred ground because nearly 50,000 soldiers died there during the infamous Civil War battle.

“I used to take my kids there, and I remember having this eerie sense of so many lives being lost in this peaceful, rural place. You know, the very dirt of the ground being watered by the blood of human beings. That’s a sacred ground.”

When she started considering other holy lands she’s visited, it dawned on her that many of them are places that most people don’t think of as holy. In “304 Washington Street,” for instance, she considers growing up in a small town just south of Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Squat and square, her pea green shingles

made her strange on our straight street

lined by wood white houses,

their faces bland and neat.

“Northeastern Pennsylvania was very beautiful at one time and then was ruined by coal mining. The land is sacred in the sense that that’s where my immigrant ancestors settled down, where they lived and died, and that’s where my family flourished,” she said.

From there, O’Donnell made a leap to the idea that parenthood can be holy ground, as can being a sibling. And if one lives a creative life, the bonds one forms with practitioners of the past are also relevant. In the Literary Islands chapter, “Flannery’s Last Day” marks the anniversary of the Aug. 3 death of Flannery O’Connor, whose family trust endowed Fordham with a grant in 2018 to promote scholarship of the writer.

Today of all days you would show up

making sure you are not forgotten.

Your suffering at the end was true,

The final chapter, Border Songs, was arguably the toughest in which to envision a connection with God, she said. The poems are meant to be “poetry of witness,” a term that the Nobel-prize winning Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz coined to describe his writing about the experience and aftermath of World War II. She wrote the poems in an attempt at accompaniment, as the world watched the horrors at the border unfold during the spring and summer of 2019.

“I felt as though it was important to meditate, to pray for, and to memorialize these people who are forgotten—people who no one cares about, people who are alienated and don’t belong,” she said.

She decided the best form to use was the triolet, a song-like poem which features several lines that are repeated several times.

“The idea is to create this haunting incantatory effect, particularly when the poem is read and listened to out loud,” O’Donnell said.

One of the first ones she wrote, “Border Song #2,” was inspired by a report that immigrants who were taken into custody were having their rosary beads confiscated.

They confiscate your rosary when you come.

I cannot go to sleep without one.

Thumbing each bead until the night is done.

They confiscate your rosary when you come.

She penned 15 triolets in short order.

“I didn’t have to look very hard. Every day, there was a new outrage, a new photograph or quotation that I would see in the news that would trigger another triolet,” she said.

She noted that in his 1946 book Man’s Search for Meaning, Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl declared that God was with him in the concentration camp, “suffering and dying with us every day.”

“That sense of God dwelling in brokenness and in sorrow and horror as well as in the sunny places that we remember happily—that’s part of what this book is about,” she said.

“There is divinity in everything—even in those dark places that we don’t necessarily want to be. There are times when we have to celebrate the darkness, and some of these poems attempt to do that.”