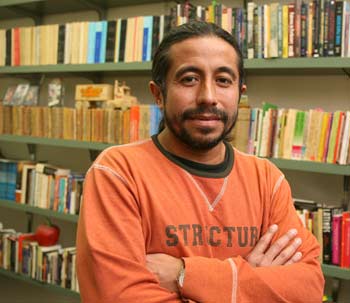

Photo by Michael Dames

O. Hugo Benavides, Ph.D., doesn’t see dead people, but he does see things that others miss.

Benavides, an associate professor of anthropology at Rose Hill and director of the master’s program in humanities and sciences, has devoted seven years to examining seemingly superficial facets of life in South America and the United States. What he has found are deeper meanings that shed light on society’s power structures.

“I’ve always been very intrigued with the nature of political domination, and how people live under conditions that seem unacceptable and exploitive, and how they make sense of that,” he said.

In his third book, Drugs, Thugs And Divas: Telenovelas and Narco-Dramas in Latin America (University of Texas Press, 2008), Benavides offers close readings of Latin American soap operas called telenovelas. Although similar in style to American sit-coms, in substance they offer serious yet subtle critiques of present-day South America, he said.

For example, he cited Xica, a Brazilian soap opera set in the 17th century when the country was still a slave territory. Benavides said he first found the show to be exploitive. Although the heroine was a black former slave who married a local governor, many of the ex-slaves were half-naked and the acting was overly melodramatic.

But a closer look revealed that the show was really dealing with taboos about racism and colonialism that are normally not talked about publicly.

“So the telenovela was able to go under the radar by putting on this surface reality, this façade, that everybody can relate to and say, ‘Oh, this is safe. There’s nothing wrong here,’” he said. “But underneath, you have the white owners being completely obsessed with their slaves. What does that say about your obsessions and your attractions and your desires?”

Benavides said programs like Xica and Betty la fea, the Mexican predecessor to ABC’s Ugly Betty, are similar to the 1980s television shows Dynasty and Dallas, which provided a safe way for Americans to explore issues of class. In telenovelas, the overriding theme is “buenas costumbres,” or good values or norms. The actors and directors are usually promoting this theme almost inadvertently, since their first priority is to entertain.

And entertain they do. Telenovelas are wildly popular throughout Latin America, and Benavides noted that Vanity Fair actually recommended Xica, even for those who cannot understand Portuguese.

“I say this jokingly, but another anthropologist made a famous remark recently. The three things that Latin America exports are people, oil and telenovelas,” he said.

Narco-Dramas are a much more local phenomenon, originating in the Mexican states bordering the United States. As the term suggests, the shows revolve around the drug trade and the violence often associated with it.

Unlike telenovelas, the actors portray ordinary people, and the production values are decidedly lower than the average Mexican film. The characters unabashedly embrace thug culture but attempt to make things more equal in society, albeit outside the legal system. Ultimately, they’re a reflection of the local population’s struggle with poverty.

“A lot of poor people have been able to make money, and they are not connected to the good norm structure,” Benavides said. “They say, I don’t have a good education; I’m not making it in business; but there’s this elicit criminal activity that I can make money from. And that really changes the odds and the structures of mainstream society.”

Not everything that Benavides studies occurs outside the United States. This month, he’s finishing a manuscript about the role of football in post-9/11 America. He said his initial impression—that the sport has become more nationalistic and full of bravado since 9/11—became much more nuanced as he observed football more closely.

There’s a lot of tenderness in the game, he discovered, from the way that players help opponents up off the field to the way they pray when others are injured. Benavides concluded that many behaviors that seemingly go against the spirit of the game are actually part of the game.

“This is really one of those male spaces that are not very common in heterosexual societies such as ours, where men are typically not able to express emotions, are not able to show feelings toward each other,” he said.

But none of this will be up for discussion next semester in Benavides’ Dealy Hall office. Instead, he will be pursuing what he considers his most challenging assignment: a sabbatical in Peru.

There, he plans to explore race relations in the Andes. It’s a bracingly complicated subject, because unlike the United States, the native Indian population in the Andes was not decimated, but mixed with the Spaniards and North Africans who colonized the area. More than half of the population is of mixed heritage but aspires to whiteness, which makes race an extremely touchy subject.

Benavides said he wants to build on the work of JoseMaria Arguedas, the late Peruvian anthropologist who was raised by Quechua-speaking Indians. As an adult, Arguedas wrote in Spanish, but used Quechua syntax, and argued much to the consternation of his countrymen that the Quechua way of life was valid.

“His work said, ‘Look, we need to figure this out, because we can’t be torn. We can’t just repress this,’” Benavides said. “But he was also very smart in saying, ‘We can’t just say we’re Indians, because we’re not anymore. We’re this mixture. So what are we?’”

Arguedas’ story resonates with Benavides, who is a first-generation immigrant from Ecuador, brought to New York City when he was one. Although he has a successful career in academia, his skin color makes it difficult to be accepted in the United States, he said. He is not exactly welcomed in Ecuador either, as he has been gone for so long, he is considered a “half gringo.”

“With that immigrant history, I was destined to be an anthropologist, with a degree or not, just a perpetual outsider,” he said.